Like many single and childless first-time homeowners, I had no thoughts of becoming a parent when I bought my house in a neighborhood that had “potential.” Well, along came my daughter, followed a few years later by a decimated housing market and a tanking economy that is still struggling.

I’d had a good career in magazines for about 15 years and was pretty secure in my current job in higher education, so I wasn’t feeling the economic pain. I thought I’d be able to ride out the storm and do OK, especially since kindergarten was coming, lightening the financial load of costly private preschool.

But the school in my neighborhood sucked. Terribly. Plus the poor economy was having some unforeseen consequences in my community. Poverty and desperation had gotten married and were taking up violent residence close by. My home was broken into several times in a year. Some fool even came in my back window while I was in the house — and when the police finally got there 40 minutes later, they pulled a gun on me in my PJs and night hat. Every time I took my daughter out to ride her bike past our little insulated cul-de-sac, I spotted a pulled-out track of hair, chicken bones, blunt ends and used condoms.

As a woman who was on the brink of age 40 at that time, I was coming into my own and trusting my experience and my instincts. My baby could not grow up where we lived. I didn’t feel safe. Nothing was near us that would edify us intellectually or culturally. Inappropriate, revealing attire and profane language were pervasive. And the service was bad — everywhere.

Rebel With Many Causes

Growing up a suburbanite in an uncommon all-black, middle-class community, I rebelled against much of what my parents tried to instill in me, because of my ungrateful ignorance. I had been OK with living in the ’hood since I moved to Washington to attend Howard University in 1989. Spending more than 20 years unconsciously, but purposely, living in sketchy neighborhoods was coming to a rapid end, because my decisions were now affecting someone else: my child.

Having responsibility for the well-being of another person should make the toughest knucklehead — aka me — check herself. For years, I’d been running from and rebelling against a horrible high school experience. Well, horrible is relative. To this day I have not been as intellectually challenged as I was at my private lily-white high school — and I loved that level of stimulation. But developing the strategies and tactics required to survive that social scene was truly life altering for me. This was Atlanta — pre-Olympics. Georgia. You hear me? Racism, sexism and all the isms were par for the course.

Like many other African Americans who attended these types of institutions, I could write books, poems, screenplays, monologues and a 10-part series on the psychological warfare I went through. It was a nice slice of hell working in the afterschool snack bar with an admitted skinhead who called me “nigger,” having teachers underestimate my intelligence, dumbing myself down to avoid smart-alecky comments from the mean kids and being forced into friendships with every other black student in the school because we had to stick together, even if we didn’t like each other. I won’t even delve into navigating the non-dating scene, and receiving the “you talk like a white girl” attitudes when I tried to be myself, whoever that was, on my side of town.

I was angry for decades and made choices based on that rage. Some worked out (Howard University). Others (sequestering myself in suspect environments), well, not so much. It took having a child to recognize the harm I’d done to myself, and would most certainly do to her if I didn’t get over it and get it together.

Impact of Childhood Traumas

Rachel Elahee, Ph.D., a psychologist in Atlanta, says my revelation is related to a major obstacle in getting over childhood traumas. “The biggest obstacle is absolutely being aware and acknowledging the impact of those traumas,” Elahee explained. “So often I see adults who minimize the impact of traumas they experience. They think they turned out OK and it’s been no big deal.

“We don’t really get how much we’re impacted not only by traumas but also by hurt, problems and concerns that we smoothed over to be able to continue to live and function. But at our core, they are still affecting the way we operate,” she said. “You may be in denial, and you will parent in a way that is negatively impacted by failing to acknowledge that abuse or traumatic event from your youth.”

I didn’t want to inflict my issues on my daughter, so I tried a bit of therapy. In his work with traumatized clients, Washington-based psychologist Shane K. Perrault, Ph.D., uses a four-step approach that includes understanding experiences and how they are impacting them, and uncovering the decisions and ground rules they established for themselves as a result.

“Next, I try and have them re-experience the trauma (sometimes via hypnosis) so that they can encounter as they originally experienced it, which is typically vastly different from the distorted version they subsequently recreated out of fear,” Perrault said. “Finally, I attempt to process the experience with them from their current position so they can start the process of making peace with the past and get past the hurt.”

Family Legacy

Therapy was helpful for me. But what has also worked well is subjecting myself to brutal, honesty (from myself and trusted friends and family) — and remembering who I am.

My grandfather brought a lawsuit in Tuskegee, Ala., that led to the desegregation of all schools in the state. My father went to a one-room schoolhouse until he was in the eighth grade and went on to work three jobs — as an elevator operator, a cab driver and a mailman — to put himself through engineering school. My mother is a psychiatric social worker (two degrees) who graduated from law school the same year I graduated from high school.

My mother kept me in dance, softball, library programs, church groups and music lessons. She engaged my brother and me in every cultural, historical and educational opportunity that dared to open in Atlanta for our entire childhoods.

This was my legacy — and my desire for my child. I started taking a hard look at my other unconscious actions. I’d had her in music and dance since she was 2 years old. So it did not surprise me when I took a year — complete with an Excel spread sheet of 21 private, public and charter possibilities — to find an elementary school in the city that was the best fit for my child.

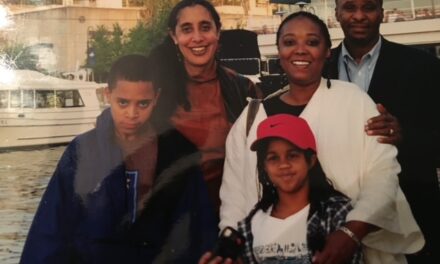

Parenting ain’t no joke. Sometimes I feel in control of this little being that God has blessed me to co-parent with her father. All of her spunk and spirit and delightful exuberance are so intoxicating — even when they regularly manifest as mischievousness. And I want to protect that part of her, but ready her as well. The world is out there.

The other day, I was dismayed when she came home and told me that one of her classmates called her Medusa. I launched into my “ignore ignorance” approach and mantra that “you know that you and your hair are beautiful, precious and special.” But her tearful response — “I know, but it hurt my feelings, Mommy” — made me see red. Not only was I remembering the pain of being called the same name for the same reason, but I was also wounded that we were already at the mean-kids stage in second grade.

And so I gave her some comeback tactics — and I felt good advising her. I normally try to dissuade her proclivity for one-upping, cutting, playing the dozens or jonin’ as we called it when I was a kid. But playground justice is real. So my suggestions were more matter of fact than in your face. I haven’t heard anything else about this particular kid. Boom!

Radical Attitude Adjustment

It’s those little wins that sometimes make a big difference in your child’s life and yours as you guestimate at this parenting thing. These days, my daughter and I are reaping the benefits of my radically adjusted attitude. We are active in our wonderfully diverse, culturally aware and politically astute neighborhood, and she attends a great school. Staying humble, prayed up and open to receiving guidance and wisdom however it shows up has been key to my growth as a person and a parent.

Apparently I am on the right track, according to Perrault.

“Changes like these or more the rule than the exception,” he said. “In fact, I refer to this ‘paradigm shift’ as evolution. Insight and experience — and in your case reality — spur us to evolve into a more balanced, reality-based perspective.

“In addition to providing a safe environment — becoming a parent means the reality of your environment, aka ‘the hood’ — takes on greater significance because playmates, school systems and other extracurricular activities (or lack thereof) are dramatically impacted by your area code. While none of these things matter much when one is single, they profoundly impact your reality as a parent.”

Elahee, agreed, adding that fluctuations in our attitudes and perspectives on parenting are to be expected because children don’t come with instruction manuals. She recommends seeking trusted advice and feedback from friends and loved ones.

“We all need somebody sometimes to bounce ideas off of even if it’s just to reassure us that we’re not crazy, or who will, in love, check us when we’re wrong or need to view a situation differently.”

That’s some good advice that I take often because my rebellious self still shows up pretty regularly. But these days, my more seasoned self runs the parenting. The wisdom that comes with growth encourages forgiving yourself, and appreciating patience and thoughtful decision-making.

Like everyone else, there’s a lot I have to work on. But my psychological wounds are healing, and I’m proud to be using my experiences and my powers for good — to parent this little wonder in my life.

Joyce E. Davis is a writer and editor living in Atlanta.