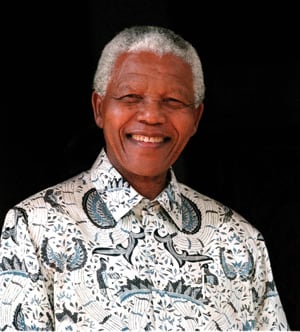

CAPE TOWN, South Africa—At Nelson Mandela’s oldest grandson Mandla’s wedding in 2004, his first, held at the family homestead in Qunu, in the Eastern Cape, everyone wanted a picture with the former South African president. At the end of a traditional ritual, the crowd dispersed and ran toward the seated Mandela. Mothers brazenly ran to dump their toddlers on his lap and then stepped back to take a quick snap. He accepted this, smiling all the while, I remember. None of his family and minders shooed people away. I stood at the back of the crowd, but like many of the guests and local villagers, I had my eye on him during the weekend festivities. I wish I had been brave enough to take a picture, a piece of him with me, just for myself.

CAPE TOWN, South Africa—At Nelson Mandela’s oldest grandson Mandla’s wedding in 2004, his first, held at the family homestead in Qunu, in the Eastern Cape, everyone wanted a picture with the former South African president. At the end of a traditional ritual, the crowd dispersed and ran toward the seated Mandela. Mothers brazenly ran to dump their toddlers on his lap and then stepped back to take a quick snap. He accepted this, smiling all the while, I remember. None of his family and minders shooed people away. I stood at the back of the crowd, but like many of the guests and local villagers, I had my eye on him during the weekend festivities. I wish I had been brave enough to take a picture, a piece of him with me, just for myself.

This has been the reaction that Mandela has inspired not just at home, but around the world. Before Mandela retired, many South Africans would grumble about why their president and revered icon had to have a photo opportunity with every visiting celebrity. There were the worthy ones, we conceded, like Bono and Oprah, but then there are the ones who seemed less deserving, like the Spice Girls. Eventually, we came to terms with the reality: Mandela did not belong to South Africa, but to the world. It was clearly a realization his family had to accept even earlier on in his life, an acceptance I witnessed firsthand at his grandson’s wedding.

That same year, when Mandela announced his formal retirement in a press conference with the parting shot “Don’t call me. I will call you,” we again accepted it. Then we went about the business of building the young country founded on his principles, along with those of his peers—ideals he was willing to die for, as he has been famously quoted during the Rivonia Treason Trial:

“We believe that South Africa belongs to all the people who live in it, and not to one group, be it black or white. … Experience convinced us that rebellion would offer the government limitless opportunities for the indiscriminate slaughter of our people. But it was precisely because the soil of South Africa is already drenched with the blood of innocent Africans that we felt it our duty to make preparations as a long-term undertaking to use force in order to defend ourselves against force. If war were inevitable, we wanted the fight to be conducted on terms most favourable to our people. The fight which held out prospects best for us and the least risk of life to both sides was guerrilla warfare.”

By retirement, he was turning 86 and already frail, yet his mind sprightly and his sense of humor alive.

It has not been so easy for the rest of the world to let go. So in the nine years while he was in retirement, defying all expectations for longevity as he did as a young firebrand many times on the run for his life, we became accustomed to foreigners still referring to him as the president of the country. As we changed from Thabo Mbeki to Jacob Zuma, it became a little irritation. But not more than the reports of fears that the country would sink into anarchy when he died, which seemed to surface every time he was admitted into hospital. The truth is as his health deteriorated Nelson Mandela had increasingly little to do with the politics of South Africa. Even South Africans accustomed to asking, “What would Mandela say? What would Mandela do?”—as they tend to do when fed up with the actions or decisions of the African National Congress government—learned to accept that there would be no response on that front.

And life has carried on without him, for better and for worse: We have seen two more presidents through successful democratic elections, much of the goals of the ANC, like housing for its citizens, sanitation, were realized. We’ve developed into an economic powerhouse after years during apartheid as an international pariah. In 2010, we successfully hosted the first soccer world cup, despite the naysaying. But we have struggled on many other fronts; AIDS became a scourge; inequality continues to rise; transforming our struggle from a race to a class war; our achievements on education have been paltry, meaning that it becomes increasingly harder to unlock the opportunities this country holds in abundance for masses of the inhabitant. We have also had cause to be ashamed and doubt whether we would ever shake off our dark past, particularly in the past few years. The killing of scores of protesting miners at Marikana was likened to Sharpeville in the 1960s when the apartheid police force mowed down a group of unarmed protesters. Then there have been the incessant xenophobic attacks that show just how prejudiced our society is and the police brutality of officers dragging suspects behind police cars that were as atrocious as the actions of the apartheid police.

Even among all this, as Mandela has died, he will not take away the whole country with him. What lies at the root of this belief by outsiders is that it does not fit in with the narrative the world, especially the developed states, has of a country in Africa. They might believe all that has been holding South Africa from anarchy is Nelson Mandela, and his passing will see us sink to our destiny. But though Nelson Mandela’s death has left a vacuum, it has not left a void. Many talk of the loss of his moral fiber, and yet forget about Desmond Tutu, a Nobel Peace Prize Laureate himself, who in the past few years has campaigned for the Dalai Lama and Aung San Suu Kyi. We live under the shade of a constitution that’s still lauded by the world and a constitutional court that can and has tried a citizen, the president and the government alike.

If we’re proven wrong, and South Africa does dissolve into anarchy as some expect, then it’s on us, not on him. We know that Nelson Mandela has given to us more than a piece of himself. His fight enabled South Africa to stand. Now it’s only for the world to accept.

Joonji Mdyogolo, a former Hubert H. Humphrey Fellow at the University of Maryland, is the former managing editor and deputy editor at O, The Oprah Magazine, South Africa. This article was reprinted by permission of Joonji and Quartz, where it originally appeared. Follow Joonji on Twitter @joonji.