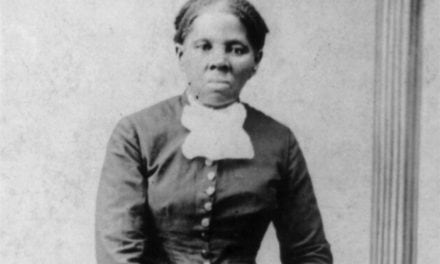

Carol Hector-Harris reflects on her heritage as she gazes out “the door of no return” at the Elmina slave fort in Ghana. “What a God-awful, infamous place,” she said.

Carol Hector-Harris, a doctoral student decades older than anyone else in the room, sat confidently on a cushioned chair. Silver twists framed a face much younger looking than her 60-something years. Her presence added an air of wisdom to the gathering of 20 young people attending a mandatory meeting for a study-abroad trip from Ohio University in Athens to Ghana.

Amid stories about how some students chose Ghana for its “cultural” appeal, Hector-Harris parted her red-rimmed lips to stun everyone with her purpose for going to Ghana.

“When I was born, I was ‘colored,’” she said. “And then before I knew it I was Negro. And then I was both colored or Negro, depending on who was talking. And then when James Brown said, ‘I’m black, and I’m proud,’ suddenly we were all black. Being black and proud finally allowed us to not be ashamed of it. Ever since then, I wanted to know who I came from.”

Hector-Harris wanted to take decades of research on her family tree and try to find the connection to her living family in Africa. After a 30-year career as an international journalist and extensive work across the African diaspora, she wanted to follow one name, Quock Martrick, her fifth great-grandfather, thousands of miles to a village in Ghana.

In Search of Family

Many African Americans have tried and failed to pinpoint their ancestry, often resulting in disappointment after decades of fruitless labor. Others won’t even try, writing off such attempts as impossible. But Hector-Harris bridged the gap that slavery created in her family hundreds of years ago.

After three weeks of things miraculously falling into place, she found her relatives in Africa. Tracing her lineage was not without obstacles, despite having a grandmother who detailed every birthdate, baby shower and bridal party in a tattered family Bible.

Hector-Harris is the youngest of four sisters and one of two who share an obsession with family history. Her older, now-retired sister, Beverly Hector-Smith, spends leisure time milling through Ancestry.com and going to weekly seminars on family geneaology. She relishes the discoveries that she and her sister have made. The duo had been picking through archives and digging up family members long before Hector-Harris thought about going to Africa.

“It’s great to have a sister who shares in your passion for discoveries,” Hector-Smith said. “Our other sisters are very ho-hum about our ancestry, just happy to listen to the stories. We had a father that was over the moon about the ancestors that he knew about.”

After taking DNA tests, infiltrating historical societies and surfing Google, Hector-Harris ended up going to Ghana by accident. Months earlier, she had glanced at the flyer-littered wall in the basement of the Scripps College of Communication. Her eyes landed on a poster from the Institute for International Journalism. It read “Ghana: Media, Society and Governance.”

“I didn’t know it was a trip at all; I thought it was a seminar so that I could learn about Ghana,” Hector-Harris said, slightly shaking her head while smiling. “Lo and behold, I learned that I could come here.”

Hector-Harris, who picked up the nickname “Queen” from her peers on the trip, is a stout, boisterous woman. She stands barely above 5 feet, but her deep chuckles and “Oh Lawds” echo much farther than she can be seen. She is the type of woman who would want to hear your entire life story, and this quality led her to finding her first family member in Africa.

During a luncheon at the African University College of Communications in Accra, Hector-Harris picked over jollof rice and spicy fried chicken while discussing her Ghana research project with a group of young women. She told them that she was part of the Ga-Adangbe ethnic group.

As the minutes ticked by and the chatting grew more intense, a short, Ghanaian woman in her 20s, named Sangmorkie Tetteh, proudly announced, “I am Ga-Adangbe!”

Hector-Harris lit up like a Christmas tree as she threw her arms around Tetteh. It turned out that they were cousins — a chance family encounter after being in Ghana just 24 hours. Tetteh was going to bring Hector-Harris to the rest of the Ga-Adangbe clan, one of the largest ethnic groups in that region.

Hector-Harris explained how word of her family search spread from one person to the next. “It’s been basically in letting people know what I’m trying to do, and people saying, ‘Well, I’m a part of that clan.’”

Whispers about the woman trying to find the Ga-Adangbe soon began to precede her travels around Ghana. Conversations at African University led to two overjoyed men at an African dance lesson and another person at a hair salon. This opened the door for a visit with village elders and historians at Big Ada about 75 miles east of Accra at the mouth of the Volta River where it enters the Gulf of Guinea.

During the visit, Hector-Harris learned that Quock Martrick’s surname had been “corrupted” from Martey, and that his first name was used interchangeably with Kwaku. At a naming ceremony, her new-found family pronounced her Akutu Martey.

Hector-Harris also found out about a huge Ga-Adangbe group right in her own backyard in Ohio. Hector-Harris was determined to find them, and it seemed that the people of Ghana were just as determined to help.

“It’s an experience like no other to look in the faces of people who have been here all along,” Hector-Harris said, reminiscing. “You just never knew who they were. And now you know that they are part of the family that you’ve always known.”

Each interaction with her family added an extra beam to Hector-Harris’s smile.

“Things were progressively falling into place for her,” said Mackenzie Miller, a student on the trip and Hector-Harris’s videographer for her research project. “You could see it in her eyes.”

Finally Home

One emotional moment for Hector-Harris took place on a balcony overlooking the Atlantic Ocean.As children splashed in the ocean and soaked up pink rays of sun shining through thick smog, Hector-Harris stood in one of the most beautiful and destructive places in Ghana: Elmina Slave Fort.

In spirit, she had found her most sought-after family member — Kwaku Martey. Hector-Harris stood at a spot of a chamber where her great-great-great-great-great-grandfather could have spent his final moments on African soil hundreds of years ago.

As the strong breeze flowed through her twisted silver hair and her faded purple African-print dress whipped against her body, Hector-Harris gazed at salty waves crashing into the weather-beaten base of the fort.

“He was here,” she whispered with quivering lips and eyes that drooped with the weight of her tears.

Hector-Harris had spent an hour locked behind gritty cell bars that might have detained Martrick and thousands of others before they were cast into the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The damp air was warm and still. The heaviness of suffering still clung to the cement that held shackles into the walls. Hector-Harris’s short frame filled the archway of the “Door of No Return,” as she stood silently, without motion.

“Who am I? Who are we? When your history in the United States begins with slavery, you know that your ancestry starts somewhere like this,” Hector-Harris said after eventually resurfacing from the slave dungeon to watch a breathtaking sunset.

“I know that at my root I’m an African person. I know what went down. I know who did what. I’m hell- bent on answering the question, ‘Who am I really?’”

But after three weeks in Ghana, meeting her extended family, Hector-Harris had found the answer. In addition to being a black woman, a sister, a wife, a mother and a well-traveled journalist, now she is a confirmed member of a clan that reaches farther than she could have imagined. She is Ga-Adangbe.

Adrienne Green is a freelance writer from Iselin, N.J., who also attends Ohio University. Carol Hector-Harris is working on a book and documentary about her family history.