A Path to a Better Life

As far back as Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman and Mary Eliza Mahoney (she became America’s first professionally trained black nurse in 1879), nursing afforded black women a measure of respect and economic security.

As one 1935 graduate put it: “My family and I knew very little about education for nurses. We did know it would be a job for me. I was determined not to pick cotton!”

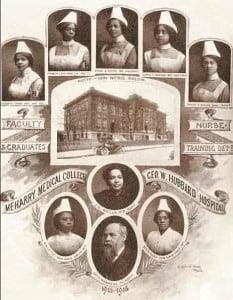

Nursing also put black women in a position to make small, but potentially powerful, changes in the way black Americans were treated. While Meharry’s historians were unable to find information on every graduate, the story of 1906 graduate Esther Maxwell Barrens illustrates the struggles and triumphs of early black professionals. A native of Pulaski, Tenn., Barrens graduated Meharry and began working in Louisville, Ky., as head nurse of the Negro Division of the Waverly Hills Sanatorium, a tuberculosis hospital, in 1907.

Like the majority of black nurses working at that time, Barrens was only considered qualified to care of other black Americans and work in a segregated facility. Even though W.E.B. DuBois had conducted an analysis of the 1900 census showing that the death rate from tuberculosis among black Americans was two to three times higher than among whites, Barrens often found herself the only nurse on duty at the poorly staffed facility.

In response, she began training nurses to work at the hospital. She also advocated for black children to continue to receive an education while hospitalized and be included in social activities.

Black nurses and physicians were desperately needed in the segregated south and the north, but that would not stop the closure of the majority of the nation’s black medical schools in 1910. In that year, the Flexner Report, published by the Carnegie Foundation, brought about a revolution in medical education that would have a severe negative impact on care for black Americans.

Flexner called for a more scientific approach to medical education and more stringent admissions standards, resulting in the closure of medical schools all over the country. But, Flexner viewed blacks as inferior, so he successfully called for the closure of five of the country’s seven black medical schools and suggested black physicians work only as “sanitarians and hygienists” for black villages and plantations.

Meharry and Howard University were the only two black institutions that survived. Many medical historians see Flexner’s work as the source of the ongoing disparities in medical education that we see even today.