More than 1,500 Americans have died after accidentally taking too much acetaminophen, the active ingredient in Tylenol. (ProPublica/Creative Commons)

During the last decade, more than 1,500 Americans died after accidentally taking too much of a drug renowned for its safety: acetaminophen, one of the nation’s most popular pain relievers.

Acetaminophen – the active ingredient in Tylenol – is considered safe when taken at recommended doses. Tens of millions of people use it weekly with no ill effect. But in larger amounts, especially in combination with alcohol, the drug can damage or even destroy the liver.

Davy Baumle, a slender 12-year-old who loved to ride his dirt bike through the woods of southern Illinois, died from acetaminophen poisoning. So did tiny five-month-old Brianna Hutto. So did Marcus Trunk, a strapping 23-year-old construction worker from Philadelphia.

The toll does not have to be so high.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has long been aware of studies showing the risks of acetaminophen – in particular, that the margin between the amount that helps and the amount that can cause serious harm is smaller than for other pain relievers. So, too, has McNeil Consumer Healthcare, the unit of Johnson & Johnson that has built Tylenol into a billion-dollar brand and the leader in acetaminophen sales.

Yet federal regulators have delayed or failed to adopt measures designed to reduce deaths and injuries from acetaminophen overdose, which the agency calls a “persistent, important public health problem.”

The FDA has repeatedly deferred decisions on consumer protections even when they were endorsed by the agency’s own advisory committees, records show.

In 1977, an expert panel convened by the FDA issued urgently worded advice, saying it was “obligatory” to put a warning on the drug’s label that it could cause “severe liver damage.” After much debate, the FDA added the warning 32 years later. The panel’s recommendation was part of a broader review to set safety rules for acetaminophen, which is still not finished.

Four years ago, another FDA panel backed a sweeping new set of proposals to bolster the safety of over-the-counter acetaminophen. The agency hasn’t implemented them. Just last month, the FDA blew through another deadline.

Regulators in other developed countries, from Great Britain to Switzerland to New Zealand, have limited how much acetaminophen consumers can buy at one time or required it to be sold only by pharmacies. The FDA has placed no such limits on the drug in the U.S. Instead, it has continued to debate basic safety questions, such as what the maximum recommended daily dose should be.

For its part, McNeil has taken steps to protect consumers, most notably by helping to fund the development of an antidote to acetaminophen poisoning that has saved many lives.

But over more than three decades, the company repeatedly fought against safety warnings, dosage restrictions and other measures meant to safeguard users of the drug, according to company memos, court records, documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, and interviews with hundreds of regulatory, corporate and medical officials.

In the 1990s, McNeil tried to create a safer version of acetaminophen, an effort dubbed Project Protect. But after the initiative failed, the company kept its experiments confidential, even when the FDA inquired about the feasibility of developing such a drug.

Later, McNeil opposed even a modest government campaign to educate the public about acetaminophen’s risks, in part because it would harm Tylenol sales.

All the while, it has marketed Tylenol’s safety. Tylenol was the pain reliever “hospitals use most,” one iconic ad said. The one “recommended by pediatricians,” said another. “Safe, fast pain relief,” its packages promised.

In written responses to questions for this story, as well as a pre-recorded statement by its vice president for medical affairs, McNeil said it has always acted to ensure its products were used safely.

“McNeil takes acetaminophen overdose very seriously, which is why we have taken significant steps over the years to mitigate the risk,” the company wrote. McNeil has engineered safety packaging and spent millions on research, education and poison control centers that advise people who have overdosed.

The company said that science on acetaminophen had evolved over time and that it had implemented safety measures accordingly. Most recently, it announced it will soon add red lettering to the caps of medicine bottles saying they contain acetaminophen and that users should read the label.

In several cases, after FDA advisors recommended the agency enact safety measures over McNeil’s objections, the company adopted them before the agency forced it to do so. The company then said it was taking such steps voluntarily. McNeil also stressed that it has always followed FDA regulations.

McNeil objected to the thrust of questions from ProPublica and This American Life, saying they indicated “a clear bias” in favor of plaintiff’s lawyers who are suing the company.

The company declined to answer questions about individual cases of death or injury. “Our hearts go out to those who have suffered harm from acetaminophen overdose, and to the families of those who lost their lives as a result,” McNeil wrote in its statement.

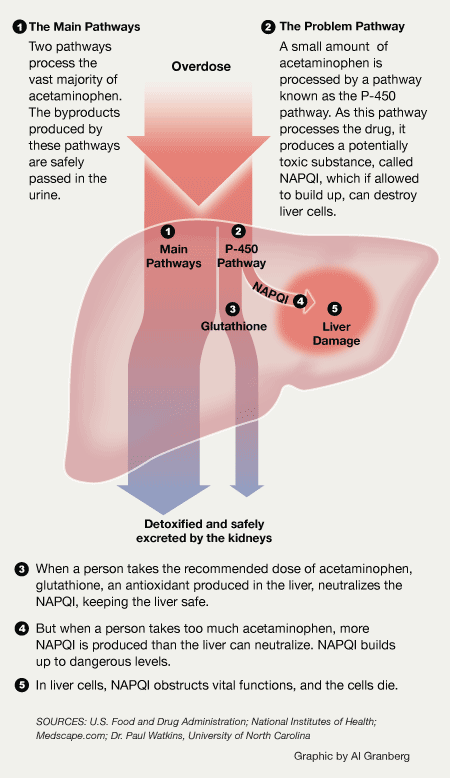

How the Liver Processes Acetaminophen

The liver uses multiple enzyme systems, known as pathways, to process acetaminophen and remove potentially toxic byproducts produced during metabolism. In the case of an overdose, these pathways become overwhelmed, allowing the byproducts to build up to toxic levels, resulting in damage to the liver. (ProPublica/Creative Commons)

FDA officials said the agency saw the benefits of keeping acetaminophen widely available as outweighing the “relatively rare” risk of liver damage or death. Some patients cannot tolerate drugs such as ibuprofen, and for them acetaminophen may be the best option, said one agency official.

The FDA has bolstered acetaminophen warnings as new science about the drug emerged, the agency said in a statement.

But FDA officials acknowledged the agency had moved sluggishly to address the mounting toll of liver damage caused by acetaminophen. They blamed changing research, small budgets, an overworked staff and a cumbersome process for changing rules for older drugs such as Tylenol slowing them down.

The agency has greater authority over prescription drugs, and it has already slapped medications containing acetaminophen with a “black box warning” that says overdosing can lead to “liver transplant and death.” Paradoxically, the same medicine sold over the counter does not tell patients that death is a possible side effect.

“Among over-the-counter medicines, it’s among our top priorities,” said Dr. Sandy Kweder, one of the FDA’s top experts on acetaminophen. “It just takes time.”

Many doctors believe in acetaminophen and some medical associations advise patients to take it for mild to moderate pain or reducing fever. “Given the number of doses given annually, the track record is incredibly safe,” said Dr. Bill Banner, a pediatrician and the medical director of the Oklahoma Poison Control Center.

Every over-the-counter pain reliever can cause harm. Even without overdosing, aspirin and ibuprofen can lead to stomach bleeding. In extremely rare cases, according to the FDA, recommended doses of ibuprofen and acetaminophen can provoke a skin reaction that can kill.

But the FDA says acetaminophen carries a special risk. About a quarter of Americans routinely take more over-the-counter pain relief pills of all kinds than they are supposed to, surveys show. That behavior is “particularly troublesome” for acetaminophen, an FDA report said, because the drug’s narrow safety margin places “a large fraction of users close to a toxic dose in the ordinary course of use.”

The FDA sets the maximum recommended daily dose of acetaminophen at 4 grams, or eight extra strength acetaminophen tablets. That maximum applies to both over-the-counter and prescription drugs with acetaminophen.

Taken over several days, as little as 25 percent above the maximum daily dose – or just two additional extra strength pills a day – has been reported to cause liver damage, according to the agency. Taken all at once, a little less than four times the maximum daily dose can cause death. A comparable figure doesn’t exist for ibuprofen, because so few people have died from overdosing on that drug.

About as many Americans take ibuprofen as take acetaminophen, according to consumer surveys from the mid-2000s.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Association of Poison Control Centers collect data on the number of deaths associated with each drug, but the figures are incomplete, making comparisons subject to question. McNeil contends the databases do not contain the information needed to draw conclusions about the relative risks of different medicines. The company and some epidemiologists maintain that these data sets undercount deaths resulting from chronic use of naproxen, ibuprofen and similar pain relievers. (More on the numbers can be found here.)

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Association of Poison Control Centers collect data on the number of deaths associated with each drug, but the figures are incomplete, making comparisons subject to question. McNeil contends the databases do not contain the information needed to draw conclusions about the relative risks of different medicines. The company and some epidemiologists maintain that these data sets undercount deaths resulting from chronic use of naproxen, ibuprofen and similar pain relievers. (More on the numbers can be found here.)

Still, the data show that acetaminophen is linked to more deaths than any other over-the-counter pain reliever.

From 2001 to 2010, annual acetaminophen-related deaths amounted to about twice the number attributed to all other over-the-counter pain relievers combined, according to the poison control data.

In 2010, only 15 deaths were reported for the entire class of pain relievers, both prescription and over-the-counter, that includes ibuprofen, data from the CDC shows.

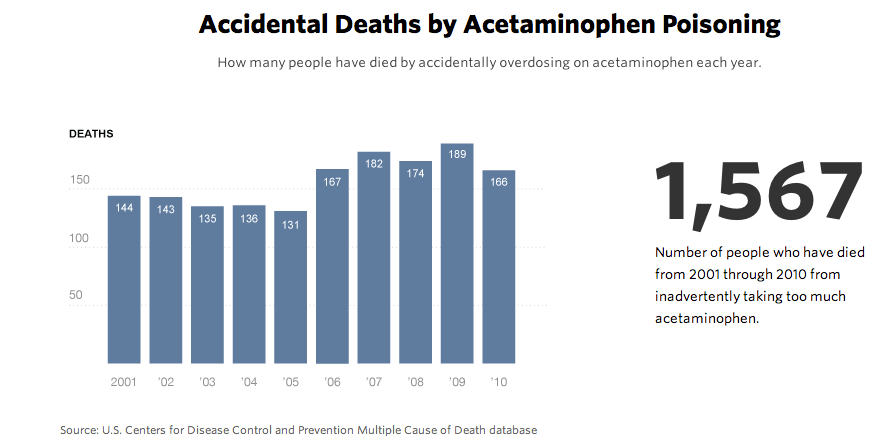

That same year, 321 people died from acetaminophen toxicity, according to CDC data. More than half – 166 – died from accidental overdoses. The rest overdosed deliberately or their intent was unclear. For the decade 2001 through 2010, the data shows, 1,567 people died from inadvertently taking too much of the drug.

Acetaminophen overdose sends as many as 78,000 Americans to the emergency room annually and results in 33,000 hospitalizations a year, federal data shows. Acetaminophen is also the nation’s leading cause of acute liver failure, according to data from an ongoing study funded by the National Institutes for Health.

Behind these statistics are families upended and traumatized and, in the worst cases, shattered by loss.

Just before Christmas 1999, 12-year-old Davy Baumle came down with a sore throat. For a week, his parents, David and Udosha Baumle, gave him Maximum Strength Tylenol Sore Throat, measuring out doses of the thick syrup.

But instead of getting better, Davy became listless. On Christmas Day, he threw up blood. His father took him to a local emergency room wrapped in a fuzzy brown blanket. A few days later, the boy was declared brain dead.

The Baumles later sued McNeil, claiming the company had failed to warn consumers of its product’s lethal danger. At trial, they testified they never gave Davy more than the recommended dose, 4 grams per day, or eight tablespoons. An expert for the company testified that lab work suggested the boy had ingested more, 6 to 10 grams, over several days.

The difference amounted to as little as 4 tablespoons a day, but the company prevailed, persuading the jury that the Baumles had not used Tylenol precisely as specified.

David Baumle said he would never have given his son the drug if he knew it was potentially lethal. At the time, the label simply warned of “serious health consequences” in case of overdose.

“They tell you it’s medicine,” he said. “They don’t tell you it can kill you.”

Reprinted with permission by ProPublica. Additional reporting by Jannis Brühl, Cora Currier, Liz Day, Sergio Hernandez, Olga Pierce, Hanna Trudo