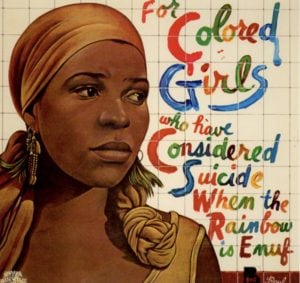

Cover of the original Broadway cast recording of “for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf.”

My intention was to just read maybe 10 pages of Ntozake Shange’s Some Sing, Some Cry while I enjoyed lunch a while ago. But 10 turned to 15 and I wasn’t done yet. After lunch, I retired to the restaurant’s outside seating on a glorious sunny, yet breezy day. Finding just enough shade, I settled in, feet propped up for what I told myself would only be five more pages — just to the end of the chapter.

I ended up on page 106 of the succulent and mammoth, multigenerational novel that Ntozake wrote with her sister, Ifa Bayeza, about a recently emancipated family in Charleston, South Carolina. Like most of Ntozake’s work, the writing has such depth and the characters are so rich that we’re intellectually full and emotionally drained long before she has the last word.

For someone who’s drawn to many things activist, historical, musical and based in the richness of people of color, well, her work is just irresistible. Ntozake Shange is bad, in the truest sense of the word. A creative visionary.

Fortunately, Ntozake has left us with a rich legacy of 19 poetry collections, six novels, five children’s books, three collections of essays and 15 plays — most notably her acclaimed Broadway “choreopoem” For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow Is Enuf. (Haven’t read For Colored Girls? It’s never too late, and it was also made into a film.)

Ntozake Shange with Atlanta writer Joyce E. Davis. (Top Photo: Adger Cowans)

I had the pleasure of meeting Ntozake at the National Book Club Conference in Atlanta one summer.You should have seen her full-back tattoo of orchids and lilies — a gift she said she gave herself for her 50th birthday. When I had the opportunity to interview her, however, I was a bit jittery about speaking to a writer who’s made such an impact with her craft. Committed writers are easy to spot. They sacrifice plenty to put work into a passion that is often terribly lonely and involves discipline, introspection and self-critiquing.

Here, in her own words, Ntozake describes discipline at its most difficult — how prayer helped her endure the painful process of “getting back to my creative self” after multiple strokes, numerous operations and bouts with mental illness. Ntozake was diagnosed with Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy (CIDP), a neurological disorder characterized by progressive weakness and impaired sensory function in the legs and arms. Born the first of four children in Trenton, New Jersey, in 1948, she later changed her name from Paulette Williams to Ntozake, which means she who comes with her own things, and Shange for she who walks like a lion. Ntozake made her transition on Oct. 27, just a week after her 70th birthday.

Biologically, she is survived by her daughter, Savannah Shange; granddaughter; two sisters, Ifa Bayeza and Bisa Williams; and brother, Paul T. Williams Jr. She also leaves a world of sisters and daughters whom she never met, but who will forever remember her words.

Rest with the angels, writer extraordinaire.

Ntozake Shange: ‘I Was Going to be an Artist Some Kind of Way’

As Told to Joyce E. Davis

When I suffered the first stroke, it was startling because one afternoon, I was perfectly fine and that evening, I couldn’t get off the floor. I was making tea in my apartment in Oakland, and my hand started shaking. I dropped the tea with the hot water in it, and I tried to crawl to the other side of the floor to get my sister on the phone.

The phone kept shaking in my hand. I tried to call my other sister on the other phone. Then I got so far away from either phone, that I couldn’t maneuver anymore. My two sisters heard each other shouting on both phones and called the Oakland police. All I remember was ending up on a gurney.

I don’t know how long I was out, but when I came to, I was incapacitated. I didn’t remember my name. I couldn’t move my left arm. I couldn’t read. I couldn’t remember how to write. So, it was quite something. I couldn’t tell you anything that was going on in my mind. It was very frightening.

During my rehabilitation in the hospital and at home, author Maya Angelou was very sweet. She sent me her children’s books to practice reading. I read those, and they were very helpful. I tried to sit at the computer, but it was wearing me out, so I had to stop. I thought if I could master the keyboard, then I would get some language skills going.

In the rehabilitation hospital, I practiced walking and cooking. I had to be able to walk, boil an egg and fry bacon before they would let me go home.

It was six months before I was able to read again. Speaking came slower. I think I had limited access to the word part of my brain. Mostly, my daughter would ask me questions and I’d nod yes or no. It took a year for me to be able to ask her questions. And I was on a walker for a good year and a half.

In terms of the writing and getting back to my creative self, there were hours of tears and just not having any idea about what was going to happen or what I’d be able to do. I knew first I had to find a reason to get my physical self better before I worried about getting better as a writer.

Between the two strokes, I had all of these surgeries for pain that had to do with my colon, which was removed. I had to find a way to overcome my physical problems at the same time I was learning how to talk again.

When things get hard, I turn to prayer. Having been in and out therapy for 45 years of being bipolar and clinically depressed, I’ve tried to commit suicide several times. But I guess I never got the hang of it, because I’m still here. What got me through those dark times was prayer.

I learned from my mother, who would improvise these long, long prayers. She would pray for me to be healthy and to be a good mother. So every once in a while, I call Savannah, my daughter, and say, ‘Come pray with your mother.’ And we’ll just pray on the phone.

That praying extemporaneously has always been extremely helpful to me. I asked my Buddhist priest to come and pray over me when I was in intensive care after the second stroke. She said a prayer that you have to say 700 times — and she did.

If you’re ever in a situation where an illness is threatening to rob you of the essence of who you are, pray and get some help quickly — because you have to begin planning your new life with whatever skills you have left.

Initially, I’d hoped just to be able to walk and talk and deal with my child. When I wasn’t sure if I’d be able to write again, I decided I’d take a welding class. And that made me really very proud because I could deal with something that was very dangerous, heavy, required a lot of attention and was in a field that I wasn’t involved in before, but loved very much.

I was going to be an artist some kind of way. Now I’ve finished a book with my sister, and books of essays and poetry. I’ve added a new poem to this next version of For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf, my choreopoem, which has been published since 1973 and performed more than 10,000 times in North America. And I’m working on a collection of short stories.

What’s fueling this creativity? The joy and wonder of still being alive.

Joyce E. Davis is a writer living in Atlanta.