Long before Venus and Serena Williams, Billie Jean King or Arthur Ashe picked up a tennis racket, Althea Gibson reigned supreme on the court, winning 11 Grand Slams and roughly 100 other titles worldwide.

Gibson, who appears on one of the newest Forever postal stamps, was thrilled to see her sons and daughters in tennis follow in her footsteps. She believed that records were meant to be broken, but it took four decades for another black tennis player to catch up to her back-to-back national and international championships. And she still holds the record for winning 10 consecutive singles titles in the American Tennis Association (ATA), which was founded in 1916 and is the oldest black sports organization in history.

In 1957 and 1958, Gibson won the singles titles at Wimbledon and the U.S. National Championships, now known as the U.S. Open. Venus Williams repeated the feat in 2000 and 2001, but no one will probably ever break Gibson’s ATA record from 1947 to 1957 because she broke enough racial barriers in the elite sport of tennis to make such an effort unnecessary.

These days, anyone who even shows such potential will automatically start swinging his or her racket on courts at Flushing Meadows, New York, home of the U.S. Open, or at the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club, where Wimbledon winners are crowned.

Nothing was automatic in Gibson’s day. It took a lot of blood, sweat and tears on the part of Gibson and her legions of supporters to help her become the Queen of Tennis, as both an amateur and professional athlete. The same type of behind-the-scenes machinations that it took for Jackie Robinson to integrate baseball when he stepped onto the diamond at Ebbets Field as a darker Brooklyn Dodger in 1947 came into play when Gibson integrated tournament tennis by competing at the U.S. Nationals in 1950 and Wimbledon in 1951.

In Gibson’s glory days, she was inundated with letters and telegrams from all over the world in assorted languages. At least 100,000 people came from near and far to shower her with confetti and strips of paper during a ticker-tape parade down the Canyon of Heroes in lower Manhattan after her singles and doubles Wimbledon victories in 1957.

Born in Silver, S.C., and reared in the heart of Harlem, Gibson was also celebrated as a renaissance woman. She led her alma mater, Florida A&M, to basketball championships; integrated the Ladies Professional Golf Association; recorded an album titled Althea Gibson Sings in 1958; sang on The Ed Sullivan Show; and appeared in the 1959 film The Horse Soldiers with John Wayne and William Holden.

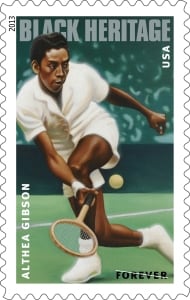

A Forever stamp of Althea Gibson, designed by Derry Noyes from a painting by Kadir Nelson. (U.S. Postal Service)

Gibson also ran for political office and made more history as the first woman and first African American to serve as a state athletic commissioner, where her duties included sanctioning wrestling and boxing matches in New Jersey for such contenders as Mike Tyson.

As she attempted a series of comebacks in tennis and golf, she also became a champion for education, fitness and equality across the lines of age, race and gender.

Gibson’s legacy is recognized annually during Black History Month and Women’s History Month. Althea Gibson tennis courts dot the country, and a bronze statue stands in her honor at those in Branch Brook Park in Newark, N.J., near her East Orange duplex apartment. Posthumous tributes have been held at the U.S. Open and elsewhere. For the postal stamp, Kadir Nelson’s oil-on-wood painting was inspired by an action shot of Gibson at Wimbledon.

In looking back on her experiences, Gibson said she “wouldn’t have missed it for the world.” Her biggest regret was that the barriers she destroyed seemed to have been re-erected behind her far too often. However, before her death in 2003 at the age of 76, she was happy to see players like the Williams sisters taking swings to make those barriers fall once and for all.

![]() Yanick Rice Lamb is co-author with Frances Clayton Gray of Born to Win: The Authorized Biography of Althea Gibson. Lamb, who teaches journalism at Howard University, is also co-founder and publisher of FierceforBlackWomen.com.

Yanick Rice Lamb is co-author with Frances Clayton Gray of Born to Win: The Authorized Biography of Althea Gibson. Lamb, who teaches journalism at Howard University, is also co-founder and publisher of FierceforBlackWomen.com.