The Making of a Fibroid

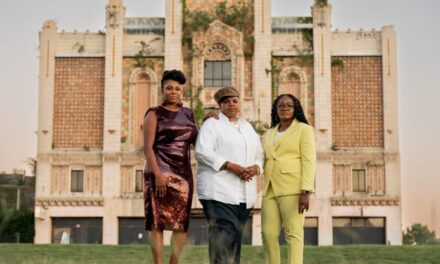

The late U.S. Rep. Stephanie Tubbs Jones, D-Ohio, championed the cause of fibroids on Capitol Hill. (Public Domain)

Like all great battles, the war against fibroids has a hero — the late Ohio congresswoman Stephanie Tubbs Jones. “She was struck by how many women, especially younger women were suffering, so she introduced the Fibroid Research and Education Act in 2003,” says former legislative aide Nicole Y. Williams of her former boss and mentor.

Jones did not live to see her work through. The bill did not pass, but she started a public conversation that is, in part, the reason scientists, working over the last five years, can now tell us how women develop fibroids.

Each fibroid (uterine leiomyomata) grows from a single adult stem cell nestled deep inside the uterine lining. Stem cells are unique in that they have the ability to continue to divide and replicate themselves in the body to maintain or repair surrounding tissue.

Problems arise when the stem cell’s programming goes haywire and a mutation develops. “That single genetic hit triggers the development of a fibroid within the myometrium — the wall of the uterus,” explains Serdar Bulun, M.D., chair of obstetrics and gynecology at the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago. Bulun leads the single National Institutes of Health–supported uterine fibroid research center in the country.

The process accelerates with every menstrual cycle, Bulun says. “The myometrium contains stem cells that divide very quickly to prepare for the possibility of pregnancy each month. Each time they divide, the mutated stem cells may multiply, giving birth to new fibroids.”

The flood of estrogen that cycles through a pre-menopausal woman’s body each month then opens the cellular door into a fibroid allowing the hormone progesterone to help the fibroid grow.

Uterine stem cells that malfunction in a variety of ways through abnormal gene expression can be found in women of all racial and ethnic backgrounds. But one small sample of 18 black women revealed 55 genes that were involved in fibroid creation and growth. The majority — 62 percent of the genes — were “associated with the silencing of tumor formation in fibroid tissues,” but were unable to do that job, according to Bulun and his team.