Life Before Dementia

Shurn says he grew up in a loving and fun home as the son of educators who were active in their Lake Michigan community, midpoint between Chicago and Detroit. His father, Joseph Shurn, rose from elementary school teacher to principal to interim superintendent. Along the way, the biology and chemistry teacher from St. Louis earned a doctorate in education. Outside the classroom, he worked to restore historic Jean Klock Park, served on the planning commission and advocated on behalf of the elderly.

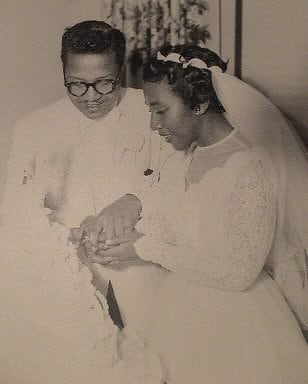

His family moved to St. Louis in 1935 when he was about 6 years old, and he grew up in the Flats, next door to his childhood sweetheart’s first cousin. Her name was Alice Marie Herndon, born in 1930 at the height of the Great Depression in St. Joseph, Benton Harbor’s twin city across the St. Joseph River. They both grew up in Union Memorial AME Church, where they were married in 1955. They shared a passion for education and the community, which would rub off on their son.

For five decades, Mrs. Shurn played piano and organ for the senior choir at Union Memorial, where she also served as music director. Armed with a bachelor’s in music and master’s in elementary education, she taught second grade for 30 years and adult education for three years after retiring in 1985. She was also a charter sorority member of the local chapter of Delta Sigma Theta.

Shortly before his 81st birthday, Joseph Shurn told a close friend, “I am trying to die, but they won’t let me.” He was speaking about his children and his wife, who drove him back and forth to dialysis treatments until the day she forgot the location of the center. Her family called the police.

“She was sitting on the side of the road lost, so that was the end of her driving,” her son said. It was also yet another signpost at the beginning of a dementia diagnosis. That was in June 2010.

Mrs. Shurn began to pass out more often, at church or at home. Her conversations would end abruptly — beyond losing one’s train of thought or the forgetfulness common as people age. With each local hospitalization, her son became increasingly frustrated as he listened to her condition being attributed to dehydration or depression over and over again.

When she fell into the Christmas tree, Shurn said, “I’m like this is it.” He called a doctor at the University of Chicago Medical Center and drove his mother 100 miles for a week-long stay. She ended up back at the hospital in early January after another fall. Over a month, doctors weaned her off the orthostatic hypotension medication and diagnosed her with dementia.

“At that point, she couldn’t stay by herself anymore,” said Shurn, whose father had died in October after battling cancer and kidney problems. “So I had to bite the bullet and say she’s going to come and stay with me. I’m a single guy. What do I know about taking care of a mother?”

“I had no expectations. I had none. I didn’t know what this would be like.”