“Inseparable” earned a spot on my wedding playlist in high school. Legions of other would-be brides and grooms also made that decision — even with no wedding date in sight.

“Inseparable” earned a spot on my wedding playlist in high school. Legions of other would-be brides and grooms also made that decision — even with no wedding date in sight.

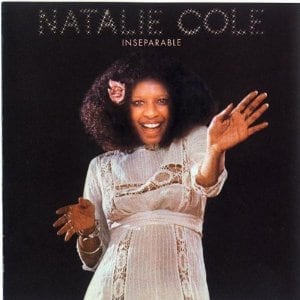

For me, “Inseparable” was Natalie Cole’s signature song. Others might beg to differ, perhaps choosing “I’ve Got Love on My Mind,” “This Will Be (An Everlasting Love)” or maybe “Sophisticated Lady (She’s a Different Lady).” However, as the title song of her 1975 debut album, “Inseparable” hit the top of the single and LP charts, catapulting Cole’s career and leading to Grammy Awards for Best New Artist and Best Female R&B Vocal Performance.

Karen McJimpson, a consultant in Detroit, and others liken Cole’s death on New Year’s Eve to losing a member of the family. Cole had a voice nearly as unforgettable as her father’s, which made it easy for listeners to gravitate toward her. That’s the way it was for me, growing up hearing my mother’s Nat “King” Cole albums on the mahogany stereo in our living room.

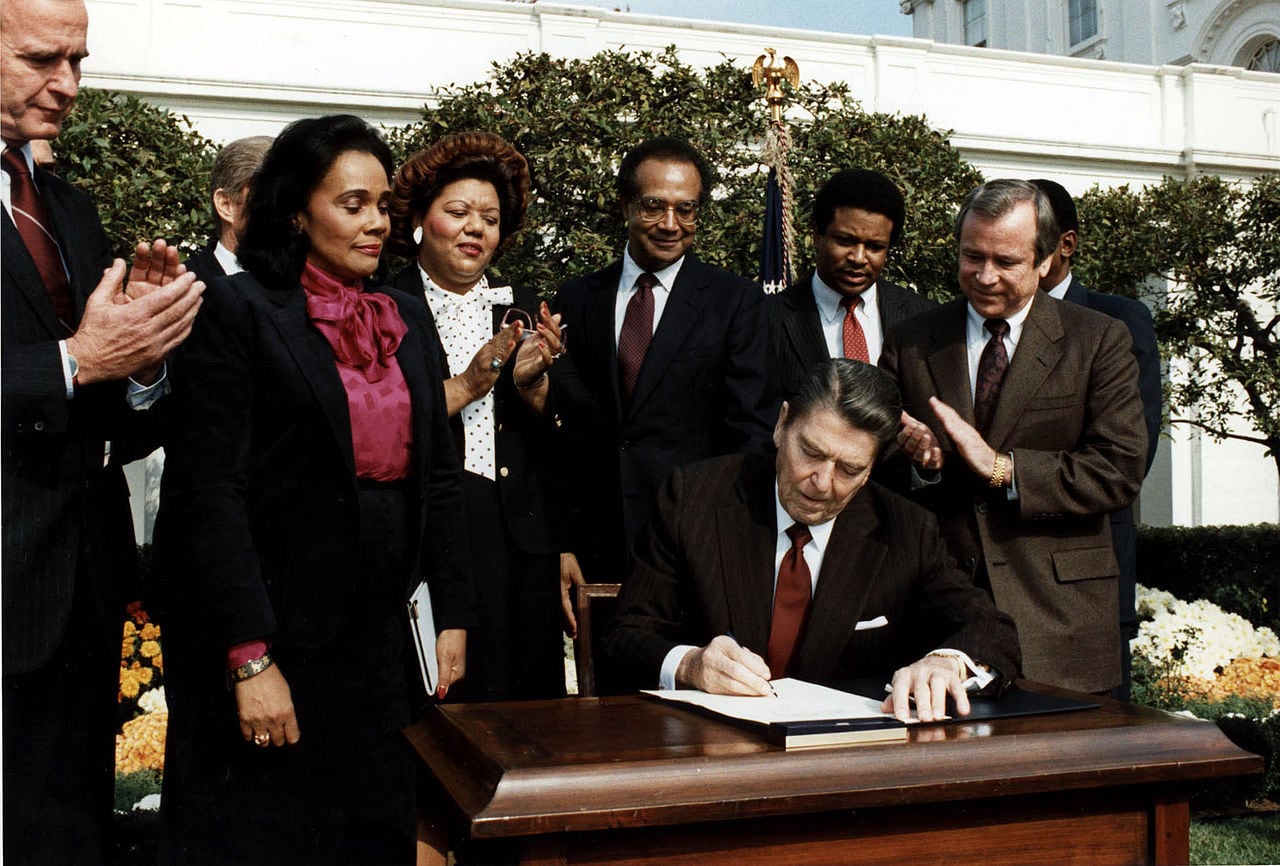

Natalie Cole sold millions of songs and won nine Grammy Awards, among other honors. Photo: Calliopejen/Creative Commons

Natalie Cole initially tried to distance herself from this natural connection to her father’s legacy to sing her own way toward stardom. Ironically, she died during the holiday season, a time when her father’s voice is ever-present, most notably on “The Christmas Song.”

Of the many times that I’ve seen Cole in concert or at industry events, what stands out most is her sold-out run at Radio City Music Hall in New York in November 1991. By then, Cole had proven herself to herself and had fully embraced her musical lineage.

Through the wonders of technology, she performed a digital duet with her father of his 1951 hit “Unforgettable” that left concert-goers spellbound. An orchestra accompanied them — Cole the daughter on stage in an off-white evening gown with Cole the father behind her on a massive screen. It almost seemed as if they had coordinated the kisses they blew at the end.

Forever a daddy’s girl with his eyes and facial features, Cole swept the 1992 Grammy Awards. Her Unforgettable … With Love album captured a half-dozen awards, including song and album of the year. This wasn’t her first duet with her father. They also sang together on a Christmas album during her childhood. She was devastated when her father died of lung cancer in 1965. He was 45; she had just turned 15.

“She gracefully grew into her own,” said Kashif, the singer, songwriter, musician and producer, who created hits for everyone from Whitney Houston to Dionne Warwick.

“I fully understand her trying to distance herself from her father and have her own spotlight, but in a sense that’s denying her pedigree and not allowing her to fully grow into the talent that she could be just by osmosis.”

“Once she embraced it, I think there was a healing that happened for her,” Kashif added. “I was thrilled when she did the Unforgettable album, because you can’t run from who your really are.”

Cole’s mother, Maria, who died of stomach cancer in 2012, was also a singer, performing with Duke Ellington, Count Basie and Fletcher Henderson. While Cole outwardly embodied the elegance and class that made her parents part of Hollywood royalty, she had been dancing along the edges of life since her days studying child psychology at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst in the early 1970s. She had graduated from smoking marijuana as a junior in high school to using LSD as a senior in college, Cole said in her 2000 autobiography Angel on My Shoulder, written with Digby Diehl.

“The drugs were just waiting to happen, a culmination of not having resolved things in my life,” said Cole, who tried everything from alcohol to heroin. “My father’s death was the beginning. It wasn’t till years later that I was able to understand that I was still grieving for him and that as ‘the-daughter-of,’ I was still walking in his shadow.”

On and off drugs since then, and in and out of rehab, she was known as a “gourmet cocaine chef” in the early 1980s before crack came to be known as crack. She was later diagnosed with hepatitis C, a liver disease, which she attributed to her days shooting up heroin. As a result, she underwent chemotherapy to treat the hepatitis, which wrecked her kidneys, requiring dialysis and then a kidney transplant in 2009. (See “Waiting for an Organ, below.)

This cascade of health problems contributed to Cole’s death on Thursday at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, her family said in a statement released by Associated Press. The 65-year-old is survived by her son, Robert Yancy, from the first of her three marriages; and younger twin sisters, Timolin and Casey. Her brother, Nate Kelly Cole, died of AIDS in 1995, and her older sister, Carole “Cookie” Cole, who encouraged her through the hepatitis C diagnosis, died of lung cancer on the day of her organ transplant.

Kashif doesn’t believe that Cole’s drug use tarnished her career and legacy, but acknowledged that “her body of work could have been much bigger had she not gone through that particular struggle.”

“We all go through our struggles, whatever our struggles are, and we have to pick up the pieces and keep going,” he said. “And certainly she did that – she picked up the pieces and kept going. That’s all that matters.”

Despite the ups and downs, Cole sold millions of songs and won several awards, including nine Grammy Awards. She recorded hits in a range of genres and sang in Spanish, earning three Latin Grammy nominations for her 2013 album, Natalie Cole en Español. She also acted in guest television roles and a made-for-TV movie of her life.

Kashif said that he was initially in disbelief when he heard of Cole’s death and that he checked to make sure that the news was indeed true. “It was a sad moment,” he said. “It put a damper on my day, because I felt that we had lost another hero and another enormous talent.”

“She had a great, great impact on young female singers,” Kashif said, possibly as great, but in a different way, as Aretha Franklin, Whitney Houston, Dionne Warwick or Chaka Khan.

“She has her own place,” he explained. “She’s very unique in her own right. She straddled two genres and really did it gracefully – R&B and jazz.”

Early in her career, Cole felt that her idol, Aretha Franklin, was dismissive of her talent. However, Franklin revealed in a statement that Cole’s death moved her to tears. Natalie Cole, Franklin said, was “one of the greatest singers of our time.”

The Queen of Soul also paid tribute to Cole during a concert at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., where she asked for a moment of silence, calling her “lovely” and gifted.”

“We will always remember this very classy and sophisticated lady,” Franklin said during her vocal and piano rendition of “Inseparable.”

“Thank you for all the great music, Natalie. God bless you.”

Yanick Rice Lamb, who teaches at Howard University, is co-founder and publisher of FierceforBlackWomen.com.

Waiting for an Organ

After Natalie Cole publicly appealed for a kidney on CNN’s “Larry King Live,” she was in surgery for an organ transplant just eight months later. A nurse who once took care of Cole heard the appeal and recommended the organ donation after her niece suddenly died.

However, many African Americans wait and wait for transplants until they run out of time. More than a third of the people waiting for kidneys are African American, and they are less likely to find one. Their odds of obtaining organs from living donors is 35 percent to 76 percent lower than for other groups, according to 2012 research on transplant centers in the American Journal of Kidney Diseases.

Dorry Segev, M.D., lead author of the study and a researcher at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, partly attributed the disparities to the health condition of potential donors. Dr. Segev also cited barriers to medical care, social attitudes, lack of awareness and cultural factors.

The National Kidney Foundation is trying to speed the process through its End the Wait initiative.