Naomi Wadler speaks her mind and moves people to tears at the March to Save Our Lives on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C. “I represent the African-American women who are victims of gun violence, who are simply statistics instead of vibrant, beautiful girls full of potential,” said the 11-year-old, who is a student at George Mason Elementary School in Alexandria, Va. Naomi and her classmates also organized a protest at their school, which included a lie-in representing fallen students who lost their lives to gunfire. Like other student protests, they devoted a minute for each teen who died in the Parkland, Fla., shooting. However, they added a minute for Courtlin Arrington, who died in Birmingham, Ala., outside the spotlight. Watch Naomi’s speech here, and read the full text below along with the stories of other young people who are gone too soon.

Hundreds of Thousands

March to End Gun Violence

By Montana Couser and Adrienne Perkins

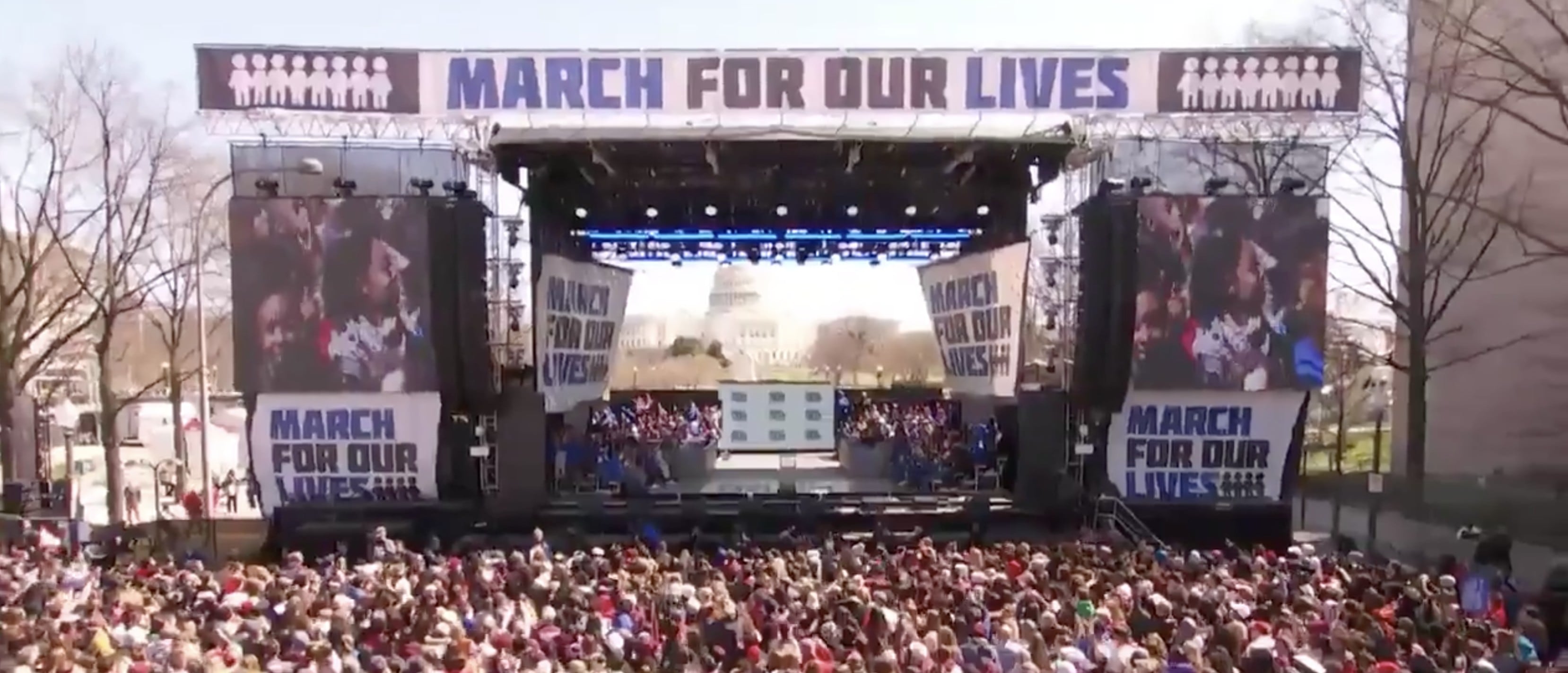

WASHINGTON (HUNS) — Hundreds of thousands marched in the nation’s capital and across the world to commemorate those who have been killed by gun violence and to demand more effective gun control legislation.

Called “March for Our Lives,” the protest was led by teenagers and survivors of the mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida.

To honor the 17 victims of the February shooting, one speaker read their name: “Alyssa Alhadeff, Scott Beigel, Nicholas Dworet, Jaime Guttenberg . . .” He saved the name of one student for last because Saturday would have been his birthday

The crowd chanted “never again” and “everyday shootings are everyday problems”

People from across the nation traveled to Washington in support of the cause. One of them was Brianna Richardson, who came from Newtown, Conn., the site of deadliest mass shooting at a public school in America. In 2012, Adam Lanza fatally shot 20 children aged 6 and 7 years old, as well as six adult staff members at Sandy Hook Elementary School.

Richardson, whose father is the president of Sandy Hook Volunteer Fire Department, said the incident inspired her to become a nurse.

“I want to help people live happy healthy lives, so that one day we don’t have people who feel so sadly that they have to do these things,” she said. After the tragedy, Richardson began volunteering and pushing for change.

Organizers estimate 800,000 people attended the march in Washington. Numerous celebrities, including Kanye West, Kim Kardashian, Arianna Grande, Common and Demi Lovato joined the demonstration.

Students and survivors of the Parkland shooting joined with students across the nation and celebrities to share their testimonies on the main stage. There was also a six-minute moment of silence for the time it took to kill the 17 victims at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School.

“Enough is enough,” Yolanda Renee King, 9, said.

One speaker on the main stage was the granddaughter of Civil Rights icon the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

“I have a dream that enough is enough and that this should be a gun free world, period,” 9-year-old Yolanda Renee King said.

The crowd at the march was very emotional and many were teary eyed at the remarks made by the speakers.

Amber Kelly, a teen mother, stood in the crowd with her son and expressed the worry she has for her son attending school.

“I’m more so scared for my son than myself,” Kelly said. “I don’t have the money to send my child to private school or home school him. How can I feel comfortable sending my son to school if I know there’s a possibility he could be shot?”

Helena Ristic, 24, who is originally from Serbia, said she decided to join the march to support the young people leading the event and to help end gun violence.

“I think this event shows that even though they’re kids, they can still make change,” Ristic said. “We all want gun violence to end.”

Lots of children were there with their parents. Many held signs and walked alongside their families.

Zachary Hill, 8, walked with his mom and two siblings and was excited he could be a part of this movement.

“I’m really happy we’re making a change for the future,” Hill said.

Aalayah Eastmond, one of the marchers and a survivor of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas shooting, said the people should not lose focus that most gun violence happens in black and Latino neighborhoods

“It doesn’t only happen in schools,” Eastmond said. “It’s been happening in urban communities forever.”

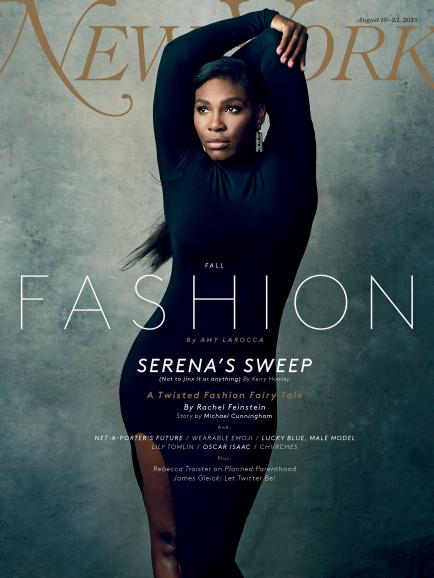

Naomi Wadler, 11, also took to the main stage with a similar message, ensuring that people of color are not left out of the conversation.

“For far too long, these black girls and women have been just numbers,” said Wadler, a fifth grader who organized a walkout at her elementary school in Alexandria, Va., earlier this month.

“I urge everyone here and everyone who hears my voice to join me in telling the stories that aren’t told, to honor the girls, the women of color who are murdered at disproportionate rates in this nation.”

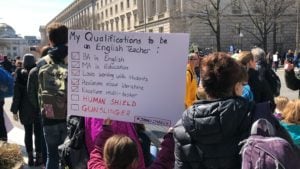

A marcher’s sign makes reference to Donald Trump’s idea to allow teachers to carry guns. (Photo: HUNS)

Shannon Douglas traveled four hours from Virginia Beach, Va., to participate in the demonstration.

“People aren’t taking this seriously,” Douglas said. “The second amendment was meant to protect your property and yourself. You don’t need an AK-47 or an SK to protect yourself. A simple handgun can do that.”

Douglas named two of the types of assault rifles protestors want banned. Supporters of gun control are also pushing for the ban of Bump stocks, an accessory that allows semi-automatic weapons to fire much more rapidly.

Leaders of the march insisted that the event was a call to action, so volunteers lined the streets to register people to vote so they can elect government officials who will support stronger gun control and remove those who do not.

“Vote them out,” an activist pleaded to the crowd.

Montana Couser and Adrienne Perkins are reporters for the Howard University News Service.

This brilliant 11-year-old girl is doing more to address gun violence and systemic racism than most adults pic.twitter.com/oRqCFMBAqz

— NowThis (@nowthisnews) March 22, 2018

Naomi Wadler’s Way With Words

Hi. My name is Naomi, and I’m 11 years old. Me and my friend Carter led a walkout at our elementary school on the 14th. We walked out for 18 minutes, adding a minute for Courtlin Arrington, an African-African girl who was the victim of gun violence at her school in Alabama, after the Parkland shooting.

Courtlin Arrington, 17, was a graduating senior accepted into Concordia College to study nursing. She was killed in a shooting at Huffman High School in Birmingham, Ala., shortly after the mass killings in Florida, but drew less media attention.

I am here today to represent Courtlin Arrington.

I am here today to represent Hadiya Pendleton.

I am here today to represent Taiyania Thompson, who at just 16 years old, was shot dead at her home here in Washington, D.C.

I am here today to acknowledge and represent the African-American girls whose stories don’t make the front page of every national newspaper – whose stories don’t lead on the evening news.

I represent the African-American women who are victims of gun violence, who are simply statistics instead of vibrant, beautiful girls full of potential.

It is my privilege for me to be here today. I am indeed full of privilege. My voice has been heard. I am here to acknowledge their stories to say they matter, to say their names, because I can and I was asked to be.

For far too long these names, these black girls and women have been just numbers.

I am here to say NEVER AGAIN for those girls, too.

I am here to say everyone should value those girls, too.

People have said that I am too young to have these thoughts on my own.

People have said that I’m a tool of some nameless adult.

It’s not true.

My friends and I might still be 11, and we might still be in elementary school, but we know we know, we know life isn’t equal for everyone and we know what is right and wrong.

We also know that we stand in the shadow of the Capitol, and we know that we have seven short years until we, too, have the right to vote!

So, I’m here today to honor the words of Toni Morrison: “If there’s a book that you want to read but it hasn’t been written yet, you must be the one to write it.”

I urge everyone here and everyone who hears my voice to join me in telling the stories that aren’t told — to honor the girls the women of color who were murdered at disproportionate rates in this nation — I urge each of you to help me write the narrative for this world, and understand so that these girls and women are never forgotten.

Thank you.

A marcher makes her point in the nation’s capital. (Photo: Tayler Adigun/HUNS)

Gun Violence in America: Part 1

A School Shooting Every Week, One by One

By Alexa Imani Spencer

Read about Taiyania Thompson in Part 2 of this series. Naomi Wadler also mentioned the 16-year-old in her speech.

This is the first of a two-part series on the murders of teenagers throughout the United States. While the nation’s attention is focused on deaths in school shootings, most teenage murders occur daily in African-American and Hispanic neighborhoods with little fanfare or public debate.

WASHINGTON (HUNS) — As 2017 came to an end in the nation’s capital, the good news of the preceding 365 days included the city’s declining crime rate. The mayor and other city officials proudly pointed to a 15 percent drop in homicides for the previous year and a 22 percent decline for all violent crime for the same period.

Sentiments quickly changed 30 days later. Within the first month of the new year, four teenagers had been murdered — Paris DeShawn Brown, 19; Davon Fisher, 17; Stephen Slaughter, 14; and Taiyania Aaliyah Thompson, 16.

America is mourning the deaths of 17 killed in a Florida high school shooting, one of deadliest in history. Their deaths have prompted a national conversation about gun control and how to keep children safe in schools. Thousands will gather in Washington Saturday in response to the latest school shooting.

Lost in the debate is the fact that a similar number of children and teenagers are shot and killed every week. Instead of victims of mass murders, they are single, solitary deaths. The examples are in cities across America. More than 20 Americans between the ages of 13 and 19 are murdered every week, according to the data website Statistica.

Every major city and smaller ones have examples.

In Los Angeles, 15-year-old Miracle McGowan was killed on Jan. 12 in a drive-by shooting as she and three other people sat in a car in the Florence-Firestone neighborhood.

In Dallas, Natalie Hernandez, 14, killed Feb. 12, was fatally shot and a 16-year-old boy was wounded as they and two other Samuell High School students were sitting in a car in a city park.

In Atlanta, 17-year-old Ga’Quavious Williams was found dead in February outside of a home with a gunshot wound in the back.

Four murders of teenagers in one month is an oddity for D.C. It serves as a reminder of gun violence taking the lives of the nation’s children daily. This is a look at their lives.

Paris DeShawn Brown, shown here with his sister, was the first to die in gun violence this year in the nation’s capital. (Photo courtesy of Larry Jones.)

Paris DeShawn Brown, 19, was the first Washington resident to die of gun violence in 2018. His body was found lifeless on Jan. 10 at the 400 block of Skyland Place in Southeast Washington. He had been shot multiple times, police said. So far, no one has been arrested.

Brown lived in Ward 8, one of D.C.’s poorest communities. Unemployment consistently runs near 12 percent, according to the Office of Labor Market Research and information. Close friends knew Brown as “Paco.” They said shortly before he was shot, he had been released after three years in custody as a juvenile.

Many, including childhood companion and classmate, Larry Jones, 16, remember him as someone who naturally stood out. Jones remembers what it was like when he was released from detention.

“Everything about him was more different than any other male that I had ever met,” Jones said.

The two became friends around the age of four, he said. When Brown came home, Jones said, he immediately enrolled in Thurgood Marshall Academy, a law-themed charter school in Anacostia where Jones and Brown were reunited as classmates.

Jones said he saw a change in Brown.

“He was very spiritual,” Jones said. “That was the first thing I noticed.”

“He would say that he believed God put him through certain situations to learn a lesson. Another thing I noticed is that he was really fed up with the way society ran.”

Lena Barker, a librarian and teacher at Thurgood Marshall Academy, said Paris DeShawn Brown used the library as a refuge where he would read and write before his death. (Photo: Alexa Imani Spencer/HUNS)

While attending Thurgood Marshall Academy, Brown began to develop a newfound social and political consciousness, said Lena Barker, 32, a librarian at the school for the past five years. Brown frequented the library as a place of refuge, she said.

“Paris, rather than being bogged down by that [academic] pressure, I think he learned how to embrace difficulty,” Barker said. “But he also learned that there was a space that he could come to and let that stuff roll off of his back a little bit, and I think that was here, in the library, for him.”

Brown had an interest in African-American Studies. So, Barker gave him books to read, including David Walker’s “Appeal,” “The Willie Lynch Letter” and “Between the World and Me” by Ta-Nehisi Coates.

Everyday he sat in the same black rolling chair, Barker recalled, where he read and wrote in such a “dignified way.”

“Paris had a presence, a very special presence that I think is so hard for young black men to tap into,” Barker said. “Even in the way he would just sit in the library and just talked to me. He had no issues with being vulnerable and open.”

Over time, he shared with her some of his writings, his poetry and his music, including one of his most recent mixtapes, “Dreams of Gold.”

“I’d like to imagine that record is about what he wanted for himself and his family,” Barker said, “and I don’t mean gold in a monetary kind of way, but I mean something bright and beautiful and valuable.”

And then he was gone.

Two days after Brown’s death, Davon Fisher, 16, was killed.

Just two days after Brown was murdered, Davon Fisher, 16, was shot and killed near the corner of Riggs Road and Nicholson Street in Northeast Washington. He and two males were found wounded in a basement. A male suspect entered and opened fire. All three victims were rushed to the hospital. Fisher was the only one that didn’t survive.

Fisher was raised in the area surrounding the crime scene. His childhood home was just blocks away on the same street. Growing up, he collected nicknames, “Snacks,” “Chucky” and “Fat Glo.” He answered to them all.

Harrison Jackson, 26, watched Fisher grow up. From his front porch, he remembers Davon as a “good child” that had a natural talent for sports. Each day after school, Jackson recalled, Davon would rush to the nearby football field to practice. The sport became an outlet. Once he stopped playing, Jackson noticed a “switch” in his behavior.

“I would say when he got into the 8th grade, about to go to the 9th grade, that’s when his transition came,” Jackson said.

He started skipping school. His grades began to slide. Jackson said he tried to turn him around.

“Every time I saw him, I tried to put positive thoughts into his head,” he said.

One of the last conversations that Jackson had with Fisher was about life choices. Other young men were present. Jackson encouraged them to go to school and seek success.

“I’m just trying to get my lil homies from around here to look at life way different,” Jackson said. “You can still be the coolest kid in the world, if you’re putting positive energy into the world, because that’s what you’re going to get back out of the world.”

Robert Nickens, 45, was Fisher’s coach for a while. Nickens has served as a youth basketball coach in D.C.’s Ward 4 for 25 years. He does it, he said, “to give them an opportunity to do better in their lives.”

Nickens said Fisher had outstanding athletic ability.

“He had a really nice three-point jump shot,” he said. “That’s something that stood out about him as a basketball player.”

Nickens described Fisher was a “great kid with a big heart.” On and off the court, he kept a genuine, caring personality, Nickens said. He had hoped that Fisher would transition to playing basketball at Roosevelt High School, where he coaches. Instead enrolled into Coolidge High School.

“As he got older, it was times where he was serious about playing sports and athletics, but he didn’t get the opportunity to do that,” Nickens said.

Having known Fisher and his family for many years, Nickens thought of him as a son.

“We were really, really close,” he said. “He was someone I held dear to my heart.” The coached even nicknamed him Chucky

For the coach, his death was a painful reminder of how children sometimes “get caught up in negative things.”

“Chucky wasn’t a negative kid,” Nickens said. “He was really loved by others. His funeral told you that. It was packed. He was a great person and he touched a lot of lives on this planet before he left.”

Alexa Imani Spencer is a reporter for the Howard University News Service. She is also president of the first student chapter of the Ida B. Wells Society, which focuses on investigative reporting.