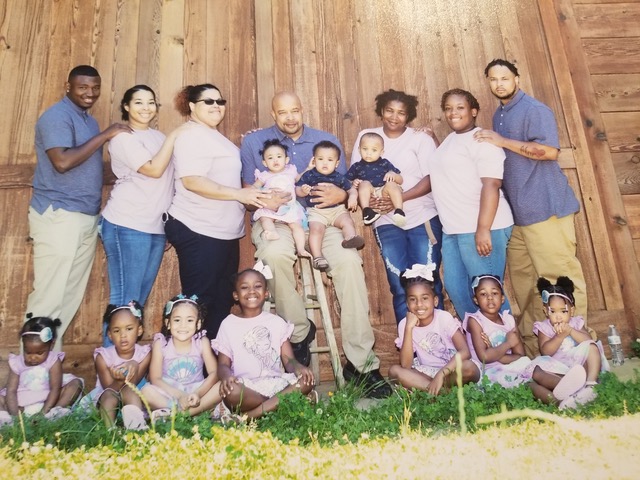

Regina Herron, her husband, children and grandchildren gather for a family portrait before the coronavirus hit their Mississippi community. While she and her husband contracted the virus, she’s happy that her children and grandchildren did not.

Systemic racism and poverty have left rural Black women at high risk for COVID-19 so they work in solidarity to thrive.

By Connie Green Freightman

Regina Dove Herron never thought the coronavirus pandemic would find its way to her door.

She and her family live on a two-acre lot, off a partially dirt road, outside Louin, a Mississippi town of fewer than 300 people.

When schools closed in March, the Head Start teacher was able to stay home and take care of her 10 grandchildren, while her son and daughters worked frontline jobs.

That same month, Mississippi reported its first case of COVID-19. By April the virus had sickened Herron, her mother and her husband, a hospital worker. Her sister, a nurse, contracted the virus later that spring.

Regina Dove Herron of Louin, Mississippi, had the coronavirus. So did her husband, mother and sister.

“The pandemic makes me worry more and pray more,” said Herron, 48. “I’m just thankful to God that my 75-year-old mother recovered and that my children and grandchildren didn’t get it.”

Initially spared as the pandemic ravaged the nation’s urban centers, many rural communities have become hot spots. For so many Black women living in those communities, the accumulated stresses from decades of systemic racism, high poverty rates and their roles as primary caregivers – and often breadwinners as frontline workers – have made them perfect targets for COVID-19.

Of the 20 U.S. counties with the highest COVID-19 death rates, six are in Georgia and Mississippi and two are majority black rural counties in Georgia, according to the COVID Tracking Project.

Rural residents tend to have higher rates of chronic health conditions, such as asthma, diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease, than urban dwellers, making them more susceptible to severe cases of COVID-19.

At the same time, many rural areas have under-resourced health-care systems, with fewer intensive care beds and doctors who specialize in critical care.

The situation is especially precarious for Black women, who tend to have more underlying health conditions, face bias in the health-care system and are less likely to have health insurance.

To cope, a growing number of Black women in rural communities are turning to mutual aid networks to help struggling families, especially where communities feel the government’s pandemic response falls short.

“On one level, COVID-19 has been devastating,” said LaTosha Brown, co-founder of the Black Voters Matter Fund. “But the beautiful thing about Black people, and the Black community in particular, is that we have always been the ones to come to our aid in crisis.”

“We now have this pandemic that’s literally killing our people, and people are losing their jobs,” Brown said. “Organizations had to respond to that need because the government wasn’t there.”

Drawing on a long tradition of solidarity not charity in Black communities, mutual aid brings together strangers and neighbors, faith-based organizations and community agencies to build a safety net for the most vulnerable.

Support ranges from the material to the spiritual – food and medicine deliveries, rental and utility payment assistance, self-care and mental health services.

The earliest Black mutual aid groups formed in the northern United States in the late 1700s to provide life, health and burial insurance, care for the sick, and support for widows and orphans. The organizations later offered education and job training.

In the 1960s and 1970s, social activism spurred new self-support initiatives, most notably Black Panther Party mutual aid programs that provided free medical care, food and education for children, and assistance with other basic needs.

When Herron’s family was in quarantine, local mutual aid organizations were there to assist.

The local Baptist association dropped off food for the family and diapers for her grandbabies. Paying it forward, Herron sews masks and donates them to seniors and anyone else who needs one.

“The community is helping each other out and taking care of the elderly,” Herron said. “That’s how we are making it. I want to do my part.”

Poverty & Inequity Set the Stage for COVID-19

While Black Mississippians like Herron make up 38 percent of the state population, they account for 45 percent of COVID-19 cases and 47.5 percent of deaths as of Nov. 8, according to the Mississippi State Department of Health. About 56 percent of people with positive cases in the state are women.

In Georgia, Black residents make up 31 percent of the state population, 34 percent of positive cases where the race is known, and they account for 40 percent of coronavirus deaths, according to the COVID Tracking Project. Women account for 52.7 percent of positive cases as of Nov. 9, according to the Georgia Department of Public Health.

Longstanding systemic health, economic and social inequities have put Black Americans at higher risk of contracting and dying from COVID-19, according to a health equity report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“COVID-19 has pulled the sheets off structural racism in the U.S. It’s been in our face all this time,” said Dr. Camara Jones, family physician, epidemiologist and former president of the American Public Health Association. “Every health disparity that we see is evidence of the impacts of racism on the health and well-being of the nation, in particular of Black people.”

Another key determinant of rural health is a lack or access to health insurance. Georgia and Mississippi, which have some of the nation’s highest uninsured rates, are among the states that did not expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

According to a report by the Kaiser Family Foundation, more than 186,000 uninsured adults in Mississippi and 518,000 in Georgia would become eligible for coverage if the states expanded their Medicaid programs under the ACA. In October, the federal government approved Georgia’s plan for a partial Medicaid expansion to roll out in July 2021 with a work requirement and without the enhanced federal funding that would go along with full ACA expansion.

“You have people who go to hospitals much sicker than they would have been if they had access to preventive maintenance in terms of health care,” said Carol Blackmon, senior consultant and co-founder of the Southern Black Rural Women’s Initiative for Economic and Social Justice. “This is a human rights issue.”

Dr. Thomas Dobbs, the state health officer in Mississippi, agreed that “everyone needs access to health care, and insurance is a key piece of that equation. We support improved access to insurance and organizations such as community health centers that help fill the gaps.”

Dobbs also acknowledges that more needs to be done to address other forms of inequity in the region, noting that the state Department of Health and its Office of Health Equity are working to address “key drivers such as structural racism, food insecurity and access to health opportunities.” Ensuring that Black communities have access to COVID-19 testing, masks and information is also part of the department’s work, he added.

“We had a pandemic before COVID-19 arrived. Our pandemic is poverty.”

As is the case in so many communities, COVID-19 is also placing a spotlight on the longstanding economic crises plaguing Black residents in rural America.

The South has the nation’s largest Black population (54 percent) and its highest poverty rate. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service report, rural Black residents had the highest incidence of poverty at 31.6 percent in 2018, while the poverty rate for rural white residents was 14 percent. Mississippi has the nation’s highest rates of poverty and food insecurity.

“We had a pandemic before COVID-19 arrived. Our pandemic is poverty. Poverty is a killer and we know it,” said Francine Jefferson, a Mississippi Poor People’s Campaign field organizer, who lost her sister-in-law to COVID-19. “You would think we would be targeted for more resources, and we get less. And yet here we are in the richest country. It doesn’t make sense.”

Poverty and poor health outcomes are an interconnected cycle, research shows, and one of the drivers of that connection is food insecurity and hunger. According to Feeding America, of the U.S. counties with the highest rate of food insecurity, 87 percent are rural and 84 percent are in the South.

Erma Wilburn’s 80-acre farm in Southwest Georgia provides fresh produce to rural Black communities that are less likely to have access to healthy food.

Coming Together to Feed the Community

Erma Wilburn quit working at a nursing home after she contracted COVID-19. She and her husband now focus on operating their farm in Worth County, Georgia.

“Despite cities surrounded by farms, [people here] have a hard time getting food because the stores are not there,” said Erma Wilburn, a semi-retired registered nurse and vegetable farmer in Southwest Georgia.

In March, she got sick with the virus while working as a nurse at an Albany nursing home. After her recovery, Wilburn, 72, quit the job. Now she and her husband focus on tending their 80-acre farm in Worth County and operating Feed My Sheep at Wilburn Farms, a nonprofit that teaches young people the value of agriculture and farmland ownership.

“I want to introduce young people to farming while also providing fresh produce to people who have a lack of access to fresh vegetables,” said Wilburn, who lost a sister-in-law and brother-in-law to the virus. “I’m engaged in this work now, and it gives me a lot of satisfaction.”

Across the South, many others are doing the same.

In response, the Black Voters Matter COVID-19 Mutual Aid and Emergency Relief Self-Determination Fund has raised nearly $500,000 to support community-based programs in Mississippi, Georgia and eight other states. One focus is food insecurity.

In Mississippi, the Mileston Cooperative Association makes weekly deliveries of food, cleaning and paper products to about 100 senior citizens and families with children in Holmes County.

The Black farmers cooperative teaches students and individuals with disabilities how to plant and harvest vegetables. The students also assist with the co-op’s pandemic relief, said director Calvin Head.

In Shaw, Mississippi, Delta Hands for Hope shifted from youth after-school and summer programming to an emergency food pantry when the pandemic hit. The organization also served lunch to about 90 children three days a week over the summer

In the Black Belt of Southwest Georgia, A Better Way Grocers, a mobile store that provides underserved areas with access to fresh produce and nutrition education, partnered with the local United Way and Council on Aging, to provide free groceries to 150 families and 368 senior citizens in Albany.

SOWEGA Rising, an advocacy group based in Albany, set up a COVID-19 Mutual Aid Toolkit to help residents find local, state and federal resources for pandemic assistance.

The group also raised money to provide 100 Black businesses with personal protective equipment necessary to reopen safely, and partnered with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Farmers to Families Food Box program to distribute food boxes to families in SOWEGA’s 14-county region.

Working the Front Lines While at Risk

For centuries, Black women have had the highest labor force participation rate of all women. That work expectation, rooted in race and gender bias, extends back to slavery and the Jim Crow era, but it has not protected Black women from poverty.

According to a report by the Georgia Budget & Policy Institute, Black women are more likely to participate in the labor force than white women in the state, but they often work in low-wage jobs. As a result, Black women are about two times more likely to live in poverty than white women.

“We’re the backbone of the economy here, yet we have the highest poverty rate.”

Mississippi women make up about half of the state workforce, but they are nearly two thirds of those making the federal minimum wage of $7.25, with more than 70 percent in jobs that pay $11.50 an hour or less, according to a report by the Mississippi Black Women’s Roundtable and the National Women’s Law Center.

“We’re the backbone of the economy here, yet we have the highest poverty rate,” said Cassandra Welchlin, executive director and co-convener of the Mississippi Black Women’s Roundtable.

“Instead of having policies or having protocols in place early, because we know that Black folks and Black women are already at a disadvantage when it comes to comorbidities, they didn’t prioritize us,” Welchlin said. “All of that is very frustrating.”

Francine Jefferson of the Mississippi Poor People’s Campaign is also frustrated and still trying to make sense of her sister-in-law Clara Kincaid’s death from the virus. Kincaid was a supervisor at the Peco Foods chicken plant in Canton, Mississippi, where she had worked for 20 years.

The Holmes County resident began feeling sick in early April before the plant began providing personal protective equipment. After developing a persistent cough and difficulty breathing, she drove 40 miles to get tested for the virus in another county and was sent home.

“She died so that people could have a bucket of chicken. It’s crazy. Who gets to decide the value of us?”

Two days later, the 50-year-old mother died in her home. She left behind six grandchildren and four sons. The loss has taken a toll on everyone. Kincaid was the pillar of the family, always present at every celebration and willing to lend a hand.

The late Clara Kincaid with one of her four sons, Kenny Kincaid Jr., before his high school prom in 2016.

“It was a senseless, preventable death,” Jefferson said. “Clara was concerned about [the virus], but she was a single mom doing what she had to do to take care of her family.”

“She died so that people could have a bucket of chicken. It’s crazy. Who gets to decide the value of us?”

Black women put themselves at high risk to earn, in part because the safety net is filled with barriers to keep poor women and their families from receiving sufficient cash assistance, childcare and job-training support, policy experts say.

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), the primary cash assistance program for poor families, was launched in 1996 to move people from poverty into self-sufficiency.

According to an analysis by the Center on Budget Policies and Priorities, the welfare reform program, which includes work requirements, time limits and benefit caps, has moved more families off welfare rolls, but not out of poverty.

In 2018, for every 100 families living in poverty, only 22 received TANF cash assistance, down from 68 families in 1996.

While research shows that direct cash assistance can improve the academic, health and economic outcomes of children in poor families, TANF benefits often don’t pay enough to help families meet basic needs. The report also found that Black children are more likely than white children to live in states that spend less than 10 percent of TANF funds on basic assistance.

“A lot of that was driven by stereotypes of Black women who were considered welfare queens and other racist tropes steeped in anti-Black racism,” said Alex Camardelle, a senior policy analyst with the Georgia Budget & Policy Institute.

“Work requirements are only there to push people off of TANF when we know evidence shows that the work requirements don’t result in people finding better paying jobs and moving up the income ladder,” he added.

In response to the economic and health fallout, rural Black women are fighting back on several fronts.

In addition to the mutual aid societies, they are engaged in voter registration drives to elect leaders who would advocate for their interests, pushing for public policies to address health disparities, provide stronger worker protections, help Black businesses, improve education and pay a living wage.

“I think we will continue to press. Black women are engaged. We’re sustaining our families. We’re voting,” said state Sen. Angela Turner-Ford, chair of the Mississippi Legislative Black Caucus. “To the extent that we are speaking out, it needs to continue. It’s hard to keep hope, but I know the needs are still there.”

Wisdom, Perseverance and Loss

Nearly nine months into the pandemic with no clear end in sight and cases rising, many Black women are still reeling from the deadly virus that caught their communities off guard.

Early on, Southwest Georgia became a hot spot after COVID-19 outbreaks at two churches. More than 8,200 people have died across the state.

In early March, Melita Nichols of Leesburg, Georgia, and her 27-year-old daughter, Qunia Roberts, attended separate church services at one of those churches, the Gethsemane Worship Center.

By late March, both were admitted to Phoebe Putney Memorial Hospital in Albany, about 10 miles away. They sent texts from their hospital rooms to keep in touch.

Both ended up in the intensive care unit. Nichols, 49, received aggressive oxygen treatment. Her daughter, 27, was placed on a ventilator. Nichols was discharged on March 30 after 10 days in the hospital. Her daughter died on April 6. If she had known in advance, Nichols said she would have advised her daughter to refuse the ventilator and ask for other options.

“Any major decision that my daughter made, she talked to me about it. That was my biggest problem, to not be there for my child in the hospital,” Nichols said. “My daughter was overweight, but she had no health problems. I don’t understand why she ended up on a ventilator at 27.”

Since her daughter’s death, Nichols has used her social media platform to remind people the pandemic is not over and to take precautions.

At the time that Nichols and her daughter contracted the virus, people in their community couldn’t get a COVID-19 test without symptoms. Now people can get free tests without symptoms and contact tracers are at work in the community.

“It took a lot of death to get there. But it’s a good thing,” Nichols said. “At first, they were saying Black people couldn’t get the virus. As we see, more Black people are getting the virus. I don’t feel like the virus is going away.”