Though Aredia Taylor’s cancer is in remission, there is no cure for multiple myeloma. She wants to join a trial so she can contribute to research. (Photo: Elroy Johnson/ProPublica)

It’s a promising new drug for multiple myeloma, one of the most savage blood cancers. Called Ninlaro, it can be taken as a pill, sparing patients painful injections or cumbersome IV treatments. In a video sponsored by the manufacturer, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., one patient even hailed Ninlaro as “my savior.”

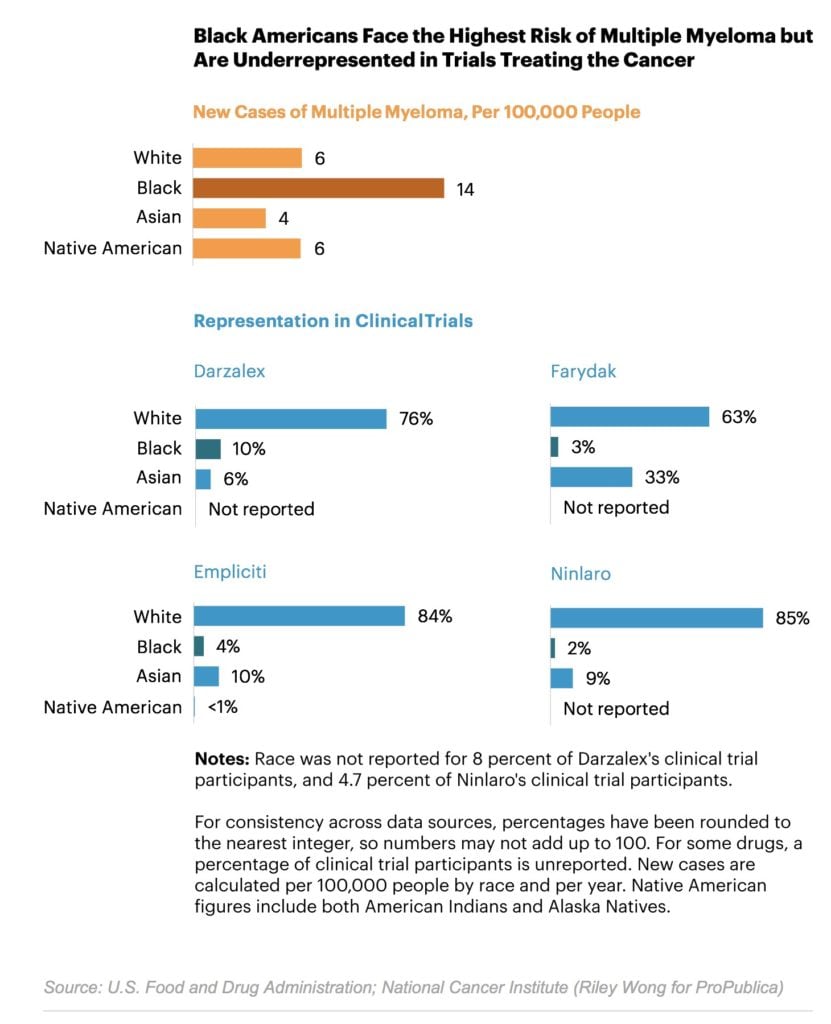

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved it in 2015 after patients in a clinical trial gained an average of six months without their cancer spreading. That trial, though, had a major shortcoming: its racial composition. One out of five people diagnosed with multiple myeloma in the U.S. is black, and African Americans are more than twice as likely as white Americans to be diagnosed with the blood cancer.

Yet of the 722 participants in the trial, only 13 — or 1.8 percent — were black.

The scarcity of black patients in Ninlaro’s testing left unanswered the vital question of whether the drug would work equally well for them. “Meaningful differences may exist” in how multiple myeloma affects black patients, what symptoms they experience and how they respond to medications, FDA scientists wrote in a 2017 journal article.

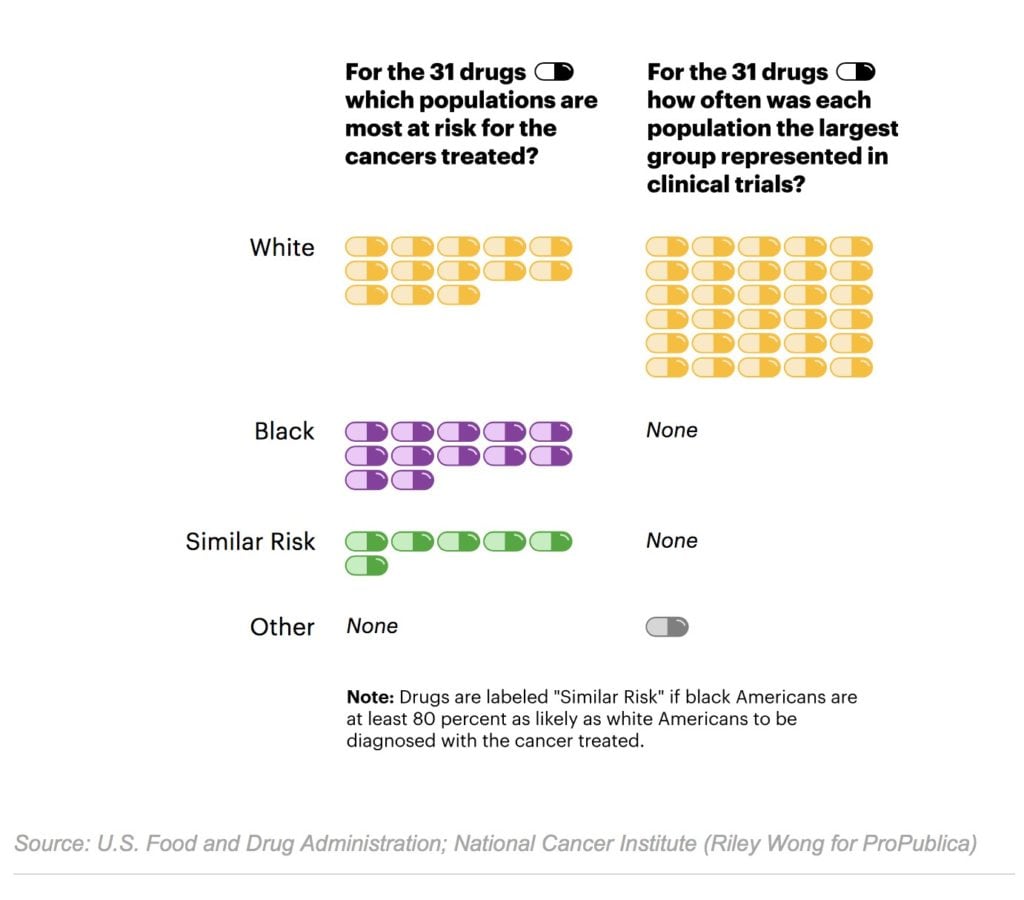

The racial disparity in the Ninlaro study isn’t unusual. Reflecting the reluctance of the FDA to force drugmakers to enroll more minority patients, and the failure of most manufacturers to do so voluntarily, stark under-representation of African Americans is widespread in clinical trials for cancer drugs, even when the type of cancer disproportionately affects them. A ProPublica analysis of data recently made public by the FDA found that in trials for 24 of the 31 cancer drugs approved since 2015, fewer than 5 percent of the patients were black. African-Americans make up 13.4 percent of the U.S. population.

As a result, desperately ill black patients who have exhausted other treatment options aren’t getting early access to experimental drugs that could extend their life spans or improve their quality of life. While unapproved treatments also carry a risk of setbacks or side effects, new cancer drugs have dramatically shifted outcomes for some patients.

Recently approved lung cancer treatments are “revolutionary,” said Dr. Karen Kelly, associate director for research at UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center. Even in the first phase of clinical testing, which is aimed at making sure a drug is safe, 20 percent of cancer patients now see their tumors shrink or disappear, up from 5 percent in the early 1990s, Kelly said.

Dr. Kashif Ali, research head at Maryland Oncology Hematology, has spent seven years recruiting patients for about 30 cancer and blood disease trials a year. He said he’s often seen minorities, including African Americans, miss out on trials because of financial hurdles, logistical challenges and their lingering distrust of the medical community due to a history of being victimized by medical experimentation.

“They’re potentially losing out on life-extending opportunities because it’s one more option they no longer have,” Ali said. “Especially when patients are in advanced stages of cancer, treatments are like stepping stones: When one stops working, you move on to the next.”

Not joining a trial can mean “you’ve lost life expectancy,” he said.

Pat Conley, a 72-year-old retired business analyst whose multiple myeloma relapsed last year, has never participated in a clinical trial. She was interested several times and didn’t meet the criteria. Now she’s eligible for one, but worries about the burden of regular hourlong trips from her Fayetteville, Georgia, home to the trial site in Atlanta, as well as the copays for medical tests. “They’ll want a new biopsy and Lordy, biopsies are not cheap,” she said.

Still, two drug regimens haven’t halted her cancer and she wants something positive to come from her illness. “If they don’t have African Americans to test it on, how will they know it’s going to work?” she asked. “If it doesn’t help me, it’ll help my children, it’ll help somebody else.”

Pharmaceutical companies contacted by ProPublica all said diversity in clinical trials is important to ensure that drugs meet patients’ needs. The issue “is not elevated high enough in the discussion on clinical studies,” said John Maraganore, chair of the industry group Biotechnology Innovation Organization. But he added that enrolling minorities is challenging, often for reasons beyond the manufacturer’s control, and that it would require a “public-private partnership, working with the FDA and NIH [National Institutes of Health].”

Black participation reached 10 percent in trials for only two of the 31 cancer drugs: the multiple myeloma drug Darzalex, where the figure was exactly 10 percent, and Yondelis, which treats two types of soft tissue cancer. Twelve percent of patients in the Yondelis trial were black, the highest proportion in the ProPublica study. Both drugs are made by Johnson & Johnson, which said it has an internal working group on trial diversity. The working group trains site leaders in best practices for diverse recruitment and seeks minority physicians to help run trials, since some patients prefer being treated by doctors of their own race.

Not enrolling in clinical trials is just one of many ways that African Americans trail white Americans in the quality of their health care. From diagnosis to death, they often experience inferior care and worse outcomes. Because some black Americans can’t afford the health insurance mandated under the Affordable Care Act, they remain less likely to have coverage than non-Hispanic white Americans. African Americans are 30 percent more likely than white Americans to die from heart disease. Black mothers are three to four times as likely as white mothers to die in pregnancy or childbirth, and black children are diagnosed with autism later than white children.

While the scarcity of African Americans stands out in ProPublica’s analysis, there appear to be gaps in participation of other minority groups as well. Asians were well represented in trials held in some foreign countries, but they made up only 1.7 percent of patients for drugs for which at least 70 percent of trials were conducted within the U.S. By comparison, about 6 percent of the U.S. population identifies as Asian. Almost two-thirds of the trials didn’t report any Native Americans or Alaska Natives, who together make up about 2 percent of the U.S. population. ProPublica’s analysis excluded Hispanics, because the FDA reports did not have a separate category for them until 2017 and do not distinguish between white and non-white Hispanics.

The very relationship of race to drug development is fraught with controversy. Race is primarily seen as a social concept, rather than as a product of measurable biological traits. Yet there’s growing evidence that, whether for environmental or genetic reasons, drugs may have different effects on different populations.

In 2014, the state of Hawaii sued Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. and Sanofi, the manufacturers of the blood thinner Plavix, accusing them of deceptive marketing for failing to disclose that the drug was less effective for some patients of East Asian or Pacific Islander descent. The drugmakers have denied allegations of misconduct and argue that genetic traits have not been proven to affect how well Plavix works. The case is pending. In the meantime, the FDA has added a warning to the label saying that Chinese patients are more likely to have a gene variation that renders the drug ineffective. Researchers at the University of California, San Francisco have found that a commonly used asthma medication, albuterol, doesn’t work as well for African-American and Puerto Rican children as it does for European American or Mexican children.

Inadequate minority representation in drug trials means that “we aren’t doing good science,” said Dr. Jonathan Jackson, founding director of the Community Access, Recruitment and Engagement Research Center at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. “If we aren’t doing good science and releasing these drugs out into the public, then we are at best being inefficient, at worst being irresponsible.”

The National Black Church Initiative, a coalition of 34,000 U.S. churches, urged the FDA in 2017 to mandate diversity in all clinical trials before approving a drug or device. “Simply put, the pharmaceutical community is not going to improve minority participation in clinical trials until the FDA compels them to do so via regulations,” it wrote to Commissioner Scott Gottlieb.

The FDA hasn’t done so. Although it noted in a 2013 report that a lack of diversity betrays a key ethical principle of medical research — equal justice for all — the agency has shied away from setting quotas or numerical guidelines for participation by race.

Instead, it has relied on persuasion. In its 2014 Action Plan, it said it aims to “share best practices,” to “support” industry efforts at improving diversity in clinical trials, and to “encourage” patients to participate in trials via social media, emails and blog posts.

“The FDA believes that enrollment should reflect the patients most likely to use a medical product,” spokeswoman Gloria Sanchez-Contreras said. The FDA “does not have the regulatory authority to require specific levels of minority representation in clinical trials,” although it may ask drugmakers for additional data, she said.

Dr. Rachel Sherman, the FDA’s principal deputy commissioner, said that she’s “not entirely satisfied” with minority enrollment but that clinical trials have become more diverse in other ways. Two decades ago, women and children were rarely included in drug studies. Now those groups are better represented and the FDA is working on including more minorities, she said.

Dr. Rachel Sherman, the FDA’s principal deputy commissioner, said that she’s “not entirely satisfied” with minority enrollment but that clinical trials have become more diverse in other ways. Two decades ago, women and children were rarely included in drug studies. Now those groups are better represented and the FDA is working on including more minorities, she said.

Sherman added that the agency has to balance how much information it demands from drugmakers against the need to get a drug onto the market, where it will be broadly available for all patients.

“When it comes to clinical research in this country, there’s a credit card, and there’s a limit on the credit card,” she said. “If we spend on one thing, it won’t get spent on another. We have to be judicious in what we require and what we demand and what we encourage.”

Diversity has its trade-offs. Clinical trials already cost hundreds of millions of dollars, and drugmakers say that requiring participants to be racially representative would likely add more time and expense.

“If you have a significant delay in enrollment, that would delay the medication advancing to the whole patient population, hurting everybody including the black population,” said Maraganore, who is also CEO of drugmaker Alnylam Pharmaceuticals Inc.

To offset costs caused by these delays, manufacturers might reduce the number of drugs in development, depriving some patients of experimental treatments, or raise prices, which would translate into higher insurance premiums and make new drugs even less affordable for the uninsured. Maraganore favors improving diversity through patient education — “a carrot-based approach” — rather than government regulation.

Despite these short-term expenses, eliminating racial disparities in clinical trials would ultimately save costs through disease prevention and improved treatment, according to a 2015 analysis by researchers at the University of California, San Francisco. Without FDA pressure, though, manufacturers may be unlikely to increase efforts to recruit African Americans, especially if their sights are set on a worldwide market. They can use the same clinical trial data to gain approval in the European Union, or Japan.

Takeda, which is based in Tokyo, Japan, tested Ninlaro in the U.S., Japan and 24 other countries, including Australia, Austria, Denmark, New Zealand, Sweden and others with small black populations. “Clinical trials are reflective of the ethnicity distribution in the population where the study takes place,” Phil Rowlands, head of Takeda’s oncology unit, said in an email. “While we cannot control enrollment eligibility based on the strict clinical criteria, our recruitment efforts extend to diverse patient populations, including minorities.”

Asked why Takeda didn’t pick sites with higher black populations, Rowlands said that Takeda does not “select sites with ethnicity as an eligibility criteria unless specific risk factors require that.”

Income is another reason for sparse African-American representation. Clinical trials are largely a middle-class option. A 2015 study found that patients with an annual household income below $50,000 had 32 percent lower odds of participating in a trial than patients with income above that threshold. The median household income of African Americans in 2016 was $39,490, compared to $65,041 for non-Hispanic white Americans.

Patients who can’t afford to travel long distances to a trial, take time off work or find child care are at a disadvantage. They are usually reimbursed for travel and food costs, but drugmakers are careful not to pay too much because they do not want to appear to be enticing patients to join when it isn’t in their medical interests, said Laurie Halloran, founder and CEO of a consulting firm for the drug industry.

While the experimental drug used in a study is free, any approved treatments that are part of the trial typically need to be covered by a patient’s own insurance, according to Ali, the research director at Maryland Hematology Oncology.

He recalled one black patient who was eligible for a study that entailed taking an already approved drug in combination with a new treatment. The approved drug cost $10,000 a month and the patient’s insurance charged 20 percent as his copayment, Ali recalled. The patient decided that joining the trial would be too expensive. He instead underwent chemotherapy, which was cheaper, but he didn’t tolerate it well. The patient is now considering hospice, Ali said.

Criteria for admission to clinical trials have become more stringent over the years, Mass. General’s Jackson said, and patients of color are increasingly excluded. They are more likely than white people to have other conditions such as stroke, hypertension and diabetes, which could complicate research results. Trials often want to enroll “the healthiest sick people they can find” and preclude patients with other conditions. “The wall basically gets taller and taller,” he said.

Aredia Taylor didn’t qualify on other grounds. A former U.S. Department of Agriculture supervisor for food safety inspections, she was diagnosed with multiple myeloma in 2014 and has undergone a gamut of treatment including various chemotherapy drugs and a stem cell transplant.

While the transplant drove her cancer into remission, there is no cure for multiple myeloma, and she needs to take Revlimid — a standard treatment — daily to keep the cancer at bay. The drug has given her side effects that she describes as devastating to her daily life, including diarrhea, muscle spasms and an inability to concentrate. She said she wants to stop taking Revlimid and would be willing to try an experimental treatment.

Taylor, 58, said she saw pamphlets at her doctor’s office encouraging patients to ask about clinical trials, so she asked her oncologist, Dr. Larry Anderson at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, whether she should join a study. He told her that she “wasn’t a fit,” she said. Anderson told ProPublica that most trials are seeking patients with either newly diagnosed or relapsed multiple myeloma, and since Taylor is currently in remission, she wouldn’t be accepted.

Taylor was disappointed. Knowing that African Americans like herself are especially susceptible to multiple myeloma, she’d like to be a part of developing more effective treatments.

“I want to pay it forward and be a blessing to somebody else,” she said. “I want to be one of the people that they try to do a clinical trial for, so they find a way to a cure.”

Spurred by Congress, the FDA began in January 2015 to regularly publish a “Drug Trials Snapshot” for every new drug approved, delineating the demographic breakdown for clinical trial participants by sex, race and age subgroups. ProPublica’s analysis focused on participants in trials for the 31 cancer drugs approved since then, comparing their demographics with data from the National Cancer Institute on the incidence of various cancers by race.

Eighteen of those drugs targeted cancers that are at least as likely to afflict black Americans as white Americans. On average, only 4.1 percent of patients in those trials were black. Trials for four multiple myeloma drugs, including Ninlaro, averaged 5 percent black participation.

An FDA study over a longer time period corroborated ProPublica’s findings. In a 2017 article in the journal Blood co-authored by Richard Pazdur, the FDA’s cancer chief, the agency reported that black patients on average made up 4.5 percent of participants in trials for multiple myeloma drugs since 2003. Higher enrollment of minorities in myeloma trials would have “multiple benefits,” the FDA scientists noted. Not only would “underserved populations” gain access to new therapies, but additional data could help researchers identify subtypes of the blood cancer and develop targeted treatments.

A similar pattern emerges for treatments of non-small cell lung cancer. It occurs in 56 out of 100,000 black Americans, versus 49 out of 100,000 white Americans. Yet ProPublica found that in trials for two recently approved drugs for a type of non-small cell lung cancer driven by a mutation in what is known as the ALK gene, less than 2 percent of participants were black.

Those drugs, Takeda’s Alunbrig and Genentech’s Alecensa, are approved for patients whose lung cancer has spread to other parts of the body. In trials, both drugs were able to shrink tumors, including lesions in the brain. Patients taking Alecensa lived without the disease progressing for an average of 25.7 months, more than double the 10.4 months for patients on another treatment.

“We believe that we must consider differences across all populations to deliver on the promise of personalized health care,” said Meghan Cox, a Genentech spokeswoman, adding that the drugmaker is “continuing to study patient response to Alecensa across populations in the post-marketing setting.”

Similarly, prostate cancer affects 178 out of every 100,000 African Americans, more than for any other race in the U.S., compared to 106 out of every 100,000 white Americans. Black Americans are twice as likely as white Americans to die from prostate cancer.

Yet from 2009 to 2015, in seven trials conducted for five new prostate cancer therapies, only 3 percent of participants were black, according to a study conducted by Dr. Daniel Spratt, vice chair of research for the department of radiation oncology at the University of Michigan. More recently, 11 times as many white as black participants — or 66 percent compared to 6 percent — joined trials for Johnson & Johnson’s new prostate cancer treatment, Erleada.

The FDA approved Erleada in February after trials showed patients on the drug lived an average of two years longer without their cancer spreading into other organs than if they were taking a placebo. In a J&J press release, physicians hailed Erleada’s “impressive clinical benefits” for prostate cancer patients.

J&J is “confident in the efficacy and safety data that have supported the approval” of Erleada, J&J spokeswoman Satu Glawe said.

Like Genentech, J&J and Takeda said they track drugs after approval to see if any racial differences emerge. For example, after another J&J drug for prostate cancer, Zytiga, went on the market in 2011, the company ran a new study of 100 patients, 50 black and 50 white.

“We were aware of the low number of African American men” in the pre-approval drug studies of Zytiga, Glawe said. The post-marketing study was intended “to ensure the medication was also providing clinical benefit to these patients.” In fact, it showed that black men responded better than white men to the drug.

The FDA is able to look for signs that an approved drug isn’t helping a specific population through a surveillance system launched in 2016, called Sentinel, which provides access to medical claims and other data on 200 million Americans obtained from insurers and other health providers, Sherman, the FDA’s principal deputy commissioner, said.

Still, post-marketing surveillance doesn’t compensate for lack of diversity in clinical trials. Minorities still miss out on experimental treatments — and, if they take a drug once it’s approved, may suffer unanticipated side effects.

Leaving analysis of a drug’s effect on minorities until it’s already on the market is “a hubristic assumption, unnecessarily arrogant,” Jackson said. Drugs should “work for the individuals who are the most vulnerable,” he said. “That necessarily includes racial and ethnic minorities.”

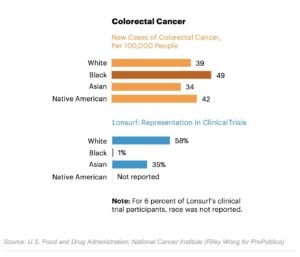

Like African Americans, Native Americans rarely enroll in clinical trials. Among the drug trials analyzed by ProPublica, 64.5 percent did not report any Native American participants, even for types of cancer that Native Americans get at similar rates as other races. (It’s possible that some Native Americans were enrolled but lumped into a generic “other” category.)

Native Americans are at higher risk of colorectal cancer than white or Asian Americans. Yet the drugmaker Taiho Oncology didn’t report a single Native American among the 800 participants in its trials for the colorectal cancer treatment Lonsurf. Taiho didn’t respond to requests for comment.

To understand how a small minority group responds to a drug, researchers might have to enroll more patients than what would be a nationally representative sample. In a trial of 100 people, two Native American or Alaska Native patients would reflect those groups’ proportion of the U.S. population, but wouldn’t give doctors enough information about race-related impacts.

Dr. Linda Burhansstipanov, founder of the Native American Cancer Research Corporation, estimated that 85 percent of Native Americans want to participate in clinical trials when informed of the opportunity. She knows several Native American patients who drove three hours each way to participate in a trial, despite losing an entire day of work.

Still, trial protocols are rarely designed with minority communities in mind, Burhansstipanov said. It has long been rumored among Native Americans, she said, that a clinical trial in the 1990s required patients to take a medication upon rising in the morning. In many Native American tribes, the first thing people do when they wake up is greet the sun with morning prayers. For some tribes, prayers can take more than half an hour. Because of the delay, the tale goes, Native American patients were kicked out of the clinical trial for violating the protocol. “The story spread and became a barrier for people to take part in clinical trials,” she said.

In addition, the history of unscrupulous medical experimentation on minorities feeds wariness of clinical trials. Angela Marshall, an internal medicine doctor and board member of Black Women’s Health Imperative, said she sees a “lack of excitement among minority communities for clinical trials, coming from a mistrust of the medical community.”

Her black patients often cite the infamous Tuskegee study, conducted from 1932 to 1972 by the U.S. Public Health Service, in which researchers knowingly withheld treatment from African American sharecroppers with syphilis in order to study the progression of the disease. Some Native Americans are similarly suspicious of the medical community, Burhansstipanov said, because the Indian Health Service (a unit of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) sterilized thousands of Native American women in the 1970s without their consent.

“The medical community has to engage in some serious trust-building initiatives,” Marshall said.

That trust is what has helped to keep Thomas Goode alive. An African American diagnosed with multiple myeloma in 2005 when he was 34, Goode has endured three stem cell transplants. In between each transplant, he participated in clinical trials, where he gained access to drug cocktails that helped bridge him to the next procedure. He counted himself lucky that he lived close to Durham, North Carolina, which is a research hub, so he was able to see specialists and take part in trials.

“I never knew anything about clinical trials, but a lot of my trust and faith was in the doctor,” he said. “I said, ‘I trust you, doctor, whatever you say.’”

Now, Goode has gone six years without a relapse. “I’m in a good place right now,” he said, “But if I didn’t try a trial, who’s to say I would still be here?”

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. This story was co-published with Stat and made available to FierceforBlackWomen.com through a Creative Commons license. Illustration by Chiara Morra/ProPublica.

A Cancer Patient’s Guide to Clinical Trials

If you’re considering whether to enroll in a trial of an experimental drug, here’s what you need to know.

By Caroline Chen

Clinical trials are a crucial step in getting new treatments to market. Before a drug can be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and released widely, manufacturers are required to carry out studies in humans to document that it is effective and to discover any side effects.

Fewer than 5 percent of adult cancer patients enroll in clinical trials. ProPublica has found that the vast majority of participants in these studies are white, even when minorities have a similar or higher risk of getting the cancer that the drug treats.

Most trials are run at academic medical centers and conducted by researchers there. Patients outside those centers often aren’t aware that clinical trials are an option, or they may wonder what joining a study entails. For patients who might consider a clinical trial, here are answers to some common questions.

Why should I join a clinical trial?

Drugs being tested in a trial often reflect the most cutting-edge technology and most current understanding of the disease. In the past decade, the cancer field has seen rapid advances in treatments, dramatically changing outcomes for some patients. Participating in a trial gives you early access to a drug that may relieve your symptoms or extend your life.

By participating in a trial, you’re also helping scientists find a treatment for your disease. It may take researchers months or even years to recruit the hundreds or thousands of patients needed for a large study. The faster the trial is fully enrolled, the sooner scientists can learn how well the drug works.

Are clinical trials a last resort?

Patients may be eligible to join a trial at any stage of their illness. Some trials seek patients who are newly diagnosed, and others are for people who have already tried other therapies.

Typically, treatments that haven’t been approved are tested first in patients who have exhausted all other options. Once approved, those drugs may then go into another round of trials for patients who are newly diagnosed.

Not all trials involve new drugs. Some test approved drugs in new combinations. Those trials may also limit eligibility based on the disease’s progression.

What are the risks of joining a clinical trial?

All trials come with risks. If a drug has not been approved, researchers may not fully understand its side effects. It’s possible that the treatment could worsen your condition or, in very rare cases, prove fatal.

Testing is usually done in three phases. The first trial is usually the smallest, and its main goal is to make sure the drug is safe. Risks of unexpected side effects may be higher in phase one trials than in phases two or three.

You should ask your doctor to discuss the possible benefits and risks of the study with you to help you decide whether to enroll.

How do I join a clinical trial?

Not every trial may be right for you. Studies have enrollment criteria, which may include your age, what stage your cancer is at and whether you are newly diagnosed or have already taken other treatments.

You don’t have to wait for your doctor to recruit you for a trial. You can ask your oncologist what studies you may be eligible for. If you are being treated at a community hospital, your doctor may need to refer you to an academic hospital that can help you enroll in a trial.

Some foundations that support the fight against certain diseases, like the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, have specially trained staff to connect patients with an appropriate trial. You can also use online search tools, such as this one from the National Cancer Institute or clinicaltrials.gov.

Will I be given a placebo?

A placebo is a “dummy” treatment that has no effect. It’s unethical to give patients a placebo if they could benefit from further treatment, so placebos are rarely used in cancer trials. If they are, the researcher who is running the study is supposed to explain that to you.

Studies that use placebos typically are comparing a new drug to what’s known as “standard of care,” which is the typical treatment that the patient would get outside of a study. One group of patients receives the standard of care plus a placebo, and another gets the standard of care plus the experimental drug.

If there are no available treatments for a disease or patients have exhausted all options, a study may compare an experimental drug to a placebo to see if it is better than no treatment at all.

Will I be paid to join a trial?

Many trials reimburse patients for expenses like travel and parking. Most do not cover lost earnings or family expenses such as day care. Each trial is different, so talk to the trial coordinator to find out what will be covered. Some foundations may provide financial support to cover costs associated with trials.

The manufacturer always provides the experimental drug for free. You have to pay for any already-approved treatments you may take as part of the study, as well as any related care such as hospital stays, but your health insurance may cover part or all of that cost.

How much time does it take to participate in a trial?

Every trial is different. Some can run for just a few weeks, others can last for years, especially if they are measuring a drug’s impact on survival.

The impact on the patient’s daily life also varies. Some studies may require you to make extra trips to the doctor or undergo additional medical tests, such as a new biopsy.

Some trials are reducing patients’ travel by sending nurses to their homes for checkups and measurements.

What is informed consent?

Informed consent is a process that gives you information about the study you are about to participate in. Before the trial starts, researchers should explain to you what the purpose of the study is, what procedures will take place, the possible benefits and risks, and the number of visits or medical tests required. They should also answer any questions you have about the study.

After you understand what the trial will entail, you’ll be asked to sign an informed consent form before taking part in the study.

Will my privacy be maintained?

As part of the informed consent process, the study coordinators should explain to you what type of information will be gathered about you, who will be able to view it, how it will be shared and how long it will be kept. When the results of the study are published, no personally identifying information, like your name, will be printed.

What if I cannot find a trial that will accept me?

It’s possible that there won’t be a trial with enrollment criteria that match your profile. In that case, keep checking with your doctor, as new trials may start in the months ahead. Also, as your circumstances change, new opportunities may arise. For example, you may not be eligible for a trial when you are first diagnosed, but you may become eligible if your cancer relapses.

Can I quit a clinical trial?

Yes, you can end your participation any time, for any reason.

What happens if the FDA doesn’t approve the drug?

If the FDA rejects the treatment, that means the manufacturer didn’t provide sufficient evidence that the drug is safe and effective. In that case, the manufacturer may stop making the drug, unless it’s approved to treat another condition. Sometimes the FDA requests more information, and the drugmaker may extend the trial or start a new one.