A collection of black women formed a sister circle around the lone black woman Democratic candidate in the final days of her campaign. But they couldn’t sustain her through Iowa and South Carolina.

(EDITOR’S NOTE: On Dec. 3, Sen. Kamala Harris of California announced that she was suspending her bid for the 2020 Democratic nomination for president. This story, which chronicled a late November push by black women to build support for Harris in Iowa and South Carolina, has been updated to include Harris announcement and otherwise reflect this development.)

By Sonya Ross

Black Women Unmuted

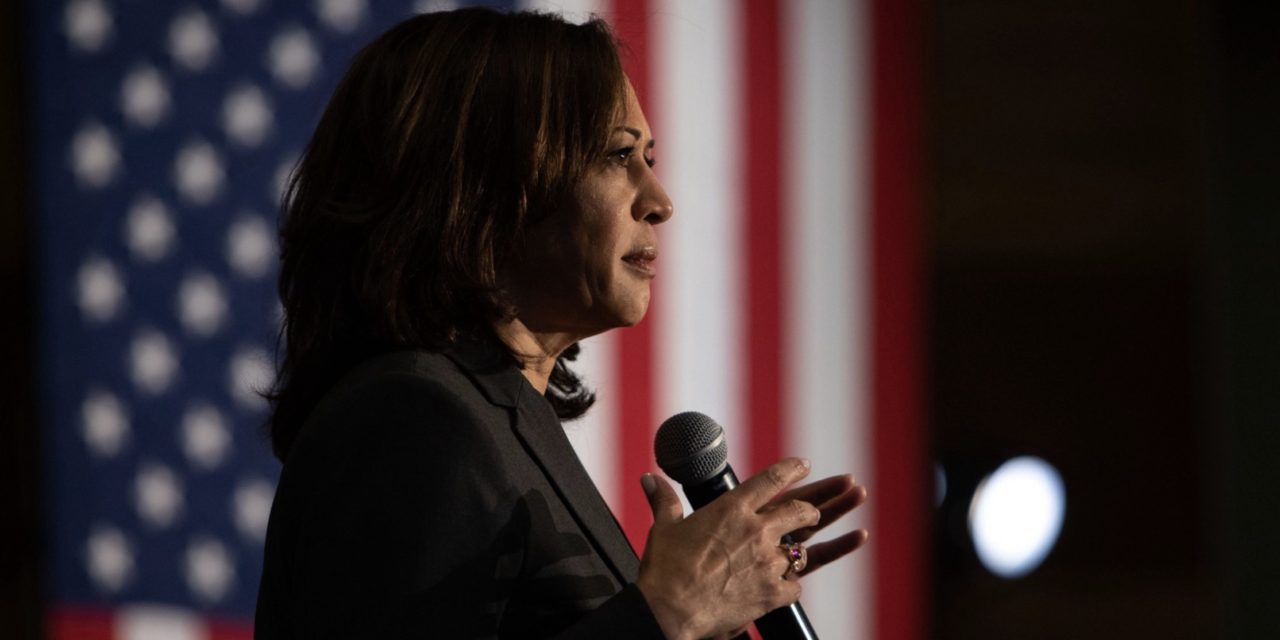

The morning after the Democratic debate at Tyler Perry’s glittering new film studio, Kamala Harris stepped onto a different stage in Atlanta, took off the gloves and took on “the donkey in the room.” Seated against a backdrop of colorful “Black Women for Kamala” posters, Harris gazed out at dozens of black women, some of them elected officials, assembled for breakfast. She told them with all honesty that she knows some voters — many of them black — think they should back a “safe” Democrat for president instead of her.

Their rationale, Harris said, is this: The need to oust Republican President Donald Trump, and tamp down the racism he fans, is too great to risk putting a black woman atop the Democratic ticket. Even post-Obama, America is not ready for that.

Harris assured the crowd that she was the best option for defeating Trump. She believed this so much that she referred to the presidency in terms of “she” and “her.” With a quick sweep of her hand to tuck her hair behind her ear, Harris pointed out that this is not a new fight. Black women typically are met with the “not ready” rap when they step up to break a barrier.

“One of the most powerful tools for a president of the United States … is when she holds this microphone,” Harris said. “With it comes the ability to change perception about so many things, including who can do what and what that looks like.”

It turned out to be a last hurrah. Two weeks later, Harris suspended her campaign. The reason, she said in a video statement to her supporters, was a lack of money.

“As the campaign has gone on, it has become harder and harder to raise the money we need to compete,” Harris said. “In good faith, I can’t tell you, my supporters and volunteers, that I have a path forward if I don’t believe I do.”

It has been the honor of my life to be your candidate. We will keep up the fight. pic.twitter.com/RpZhx3PENl

— Kamala Harris (@KamalaHarris) December 3, 2019

Harris may have been the only black woman among Democratic presidential contenders, but she was hardly out there by herself. A coterie of black women had emerged at Harris’ side to blunt her critics and curry support for her among black women.

After the Atlanta debate, they launched an all-out push for Harris, operating off a feeling that Harris was backed by more black women than she was getting credit for.

“We’re not scared. We’re not confused,” Rep. Brenda Lawrence, a Michigan Democrat, said during a Nov. 23 black women’s town hall for Harris in South Carolina. “We’re very clear that she is the woman for the job.”

Despite Harris’ departure, support from the sisters, crowned “the backbone” of the Democratic Party, remains a big deal. Harris made clear that she would continue working to ensure that the remaining Democratic candidates pay appropriate attention to the concerns of black voters.

“Our campaign uniquely spoke to the experiences of black women, and people of color, and their importance to the success and the future of this party,” Harris said. “Our campaign demanded no one should be taken for granted by any political party. We will keep up that fight, because no one should be made to fight alone.”

Glynda Carr, president and CEO of Higher Heights, the black women’s political advocacy group that endorsed Harris, had put Democrats on notice about this well before Harris left the race.

“The road to the White House and the road to 2020 is powered by us, right?” Carr said the morning after the Atlanta debate. “But this time, we’re demanding a return on our voting investment.”

Higher Heights’ public push for Harris came as the California Democrat was pushing a giant rock up a steep hill. She desperately needed to win, or show, in Iowa’s Feb. 3 caucuses. Polls consistently placed her behind former Vice President Joe Biden, her fellow U.S. senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, and a surging South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg, whose support among black voters is minuscule at best.

On top of that, Harris’ campaign was pocked by internal strife. Fundraising was tough. Introducing herself to Iowa voters was more challenging for her than others, Harris explained in the last days of her campaign, because the necessary TV ads cost more money than she could spare.

“There’s a candidate who came into the race with $10 million. That’s called start-up capital. I don’t have that kind of capital.”

Harris’ struggles echoed those met in 1972 by Democrat Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman to seek the presidential nomination of a major political party.

Chisholm also had trouble raising money and got less visibility than white male candidates. She, too, felt “the need to walk a tight rope of being perceived as ‘strong’ but not ‘difficult’ in getting her message across to the voters,” said Fredrick Harris (no relation to the senator), political science professor and director of the Center on African American Politics and Society at Columbia University.

“We know that Shirley Chisholm had a difficult time during her 1972 presidential run, and Carol Moseley Braun had challenges during her short-lived campaign in 2004,” Harris said. “We should expect no different from Kamala Harris.”

Harris’ woes were exacerbated by whispers that gnawed at her credibility with black voters: Kamala locked up black people as a prosecutor. She is indifferent to the pain of mass incarceration among black men.

“It breaks my heart,” Harris said. “Are we saying that, when people have an ability to make a decision about who will be charged with a crime … we don’t want it to be someone who comes from the same community? To reform systems, we’ve got to be everywhere. So, that’s the choice I made.”

Harris had a theory about why those whispers persist. Russian intervention in the 2016 election showed Americans are wildly susceptible to racist narratives, she said, and the purveyors of those distortions are at it again for 2020.

“My campaign has often been the number one target of Russian bots,” Harris said. “We have to figure out ways to remind folks to not get played.”

Paraphrasing the late Coretta Scott King’s observation that the fight for racial progress starts over with each generation, Harris urged her supporters at the Atlanta breakfast to be encouraged about her prospects.

“Instead of throwing up our hands, let’s roll up our sleeves. We cannot ever, as a people, afford to sit back and think everything is going to be OK.”

To that end, longtime Georgia state Rep. Mable Thomas, an Atlanta Democrat, stood and identified a handful of other elected officials in the room. Thomas asked Harris whether she would be willing to “fight for and in Georgia” for Democrats, because the people she named were willing to mobilize voters for the California senator.

“We are on the ground,” Thomas said. “We can actually help you win Georgia.”

“Yes, yes, yes yes,” Harris replied. “I intend to be a president who comes back to help you build up the state party.”

As soon as she took the stage at the town hall at Benedict College, Harris handed a folder to Trav Robertson, chair of the South Carolina Democratic Party. Inside, she said, was the paperwork for her official filing for the state’s Feb. 29 primary. As he accepted the folder, Robertson called it “a historic moment.”

“I’m out early for Sen. Kamala Harris, OK?” said actress Sheryl Lee Ralph, moderator of the forum. “We do not care this weekend if you are white, black, red, yellow, any mixed colors. We want you to vote like a black woman.”

After the Atlanta breakfast, Higher Heights threw a fundraiser for Harris in Harlem. That same day, Harris picked up an endorsement from Rep. Stacey Plaskett of the Virgin Islands, bringing to 11 the number of endorsements that Harris has secured from Congressional Black Caucus members.

“All things being equal, I’m going with the sister,” Rep. Marcia Fudge, D-Ohio, told the breakfast audience. “If we support her, she will win. Don’t ever let anybody tell you she cannot win. And don’t listen to polls because if the polls were right, I would not be sitting here now.”

Before rushing back to Washington for a meeting about a congressional report on voter suppression, Fudge dismissed the knocks against Harris’ prosecutorial record as a red herring promulgated by people seeking a reason to reject her.

“I was a prosecutor; nobody ever mentions it,” Fudge said. “I put people in jail, too. But I helped a lot of people stay out of jail, too, as did she. … We judge more harshly people who look like us than we do anyone else. It is time to be fair.”

Harris herself set the wheels for this sisterly exuberance in motion during the Nov. 20 Democratic debate. She called out the Democratic Party for neglecting black voters until “it’s, you know, close to election time.” She said it is hypocritical to applaud black women for the strong turnout that undergirded Democratic electoral gains in 2017 and 2018, then ignore their policy needs.

“When black women are three to four times more likely to die in connection with childbirth in America, when the sons of black women will die because of gun violence more than any other cause of death, when black women make 61 cents on the dollar as compared to all women who tragically make 80 cents on the dollar,” Harris said, “the question has to be, ‘Where you been, and what are you going to do? And do you understand who the people are?’”

Biden went on the defensive. He ran down a list of his black supporters — and promptly misspoke by identifying Braun as the only black woman elected to the Senate.

“That’s not true,” Harris replied. “The other one is here.”

Biden swiftly sought to fix the faux pas, saying: “No, I said the first. I said the first African-American woman.”

The moment stuck, however, and underscored a point black women have been making for years about Democrats’ benign neglect of their loyalty. Hearing that neglect explained eloquently by a black woman during a nationally televised debate drew sighs of relief.

“That was one of my favorite parts of the night for sure,” Fatima Goss Graves, president and CEO of the National Women’s Law Center, said during a Facebook Live debate recap hosted by the United State of Women.

“We can flip this a little bit and put black women at the center of the conversation,” Goss Graves said. “I would love to see what it would look like to put black women at the center, identify an agenda that actually would meet their needs, and then talk about how you’re going to fill your cabinet and key posts with black women and other women of color. It would be interesting to think in a different way for once.”

Sonya Ross is editor-in-chief of Fierce content partner Black Women Unmuted. A former White House correspondent, Ross has covered national politics as a reporter and editor for more than 25 years.

These letters from my daughters were left on the kitchen counter before they went to school this morning. They’re letters to Senator @KamalaHarris.

— Deitra Matthews (@deitramatthews) December 4, 2019

I’m grateful that my daughters had this experience. One day, I know that I’ll read about it in full colored detail.#ForThePeople pic.twitter.com/YfyupJheBU

That’s my first heartbeat! Caroline was born with #SpinaBifida & #Hydrocephalus. She’s had 2 brain surgeries – 1 to repair a spontaneous brain hemorrhage. She didn’t walk until she was almost 4. Now, she’s talking to our 46th President! Christ designed all of this!#Grateful https://t.co/YUSZHcI7YL

— Deitra Matthews (@deitramatthews) October 7, 2019