By Anna Almendrala

Lavina Wafer, 70, of Richmond, California, decided to take the vaccine after recovering from COVID-19.

In the hospital with COVID-19 in December, Lavina Wafer tired of the tubes in her nose and wondered impatiently why she couldn’t be discharged. A phone call with her pastor helped her understand that the tube was piping in lifesaving oxygen, which had to be slowly tapered to protect her.

Now that Wafer, 70, is well and back home in Richmond, California, she’s looking to her pastor for advice about the COVID vaccines. Though she doubts they’re as wonderful as the government claims, she plans to get vaccinated anyway — because of his example.

“He said he’s not going to push us to take it. It’s our choice,” Wafer said, referring to a recent online sermon that praised the vaccines as God-given science with the power to save. “But he wanted us to know he’s going to take it as soon as he can.”

Helping people accept the COVID vaccines is a public health goal, but it’s also a spiritual one, said Henry Washington, the 53-year-old pastor of The Garden of Peace Ministries, which Wafer attends.

Clergy must ensure that people “understand they have an active part in their own salvation, and the salvation of others,” said Washington. “I have tried to suggest that taking the vaccine, social distancing and protecting themselves in their household is something that God requires us to do as good stewards.”

Many Black Americans look to their religious leaders for guidance on a wide range of issues — not just spiritual ones. Their credibility is especially crucial on matters of health, as the medical establishment works to overcome a legacy of experimentation and bias that makes some Black people distrustful of public health messages.

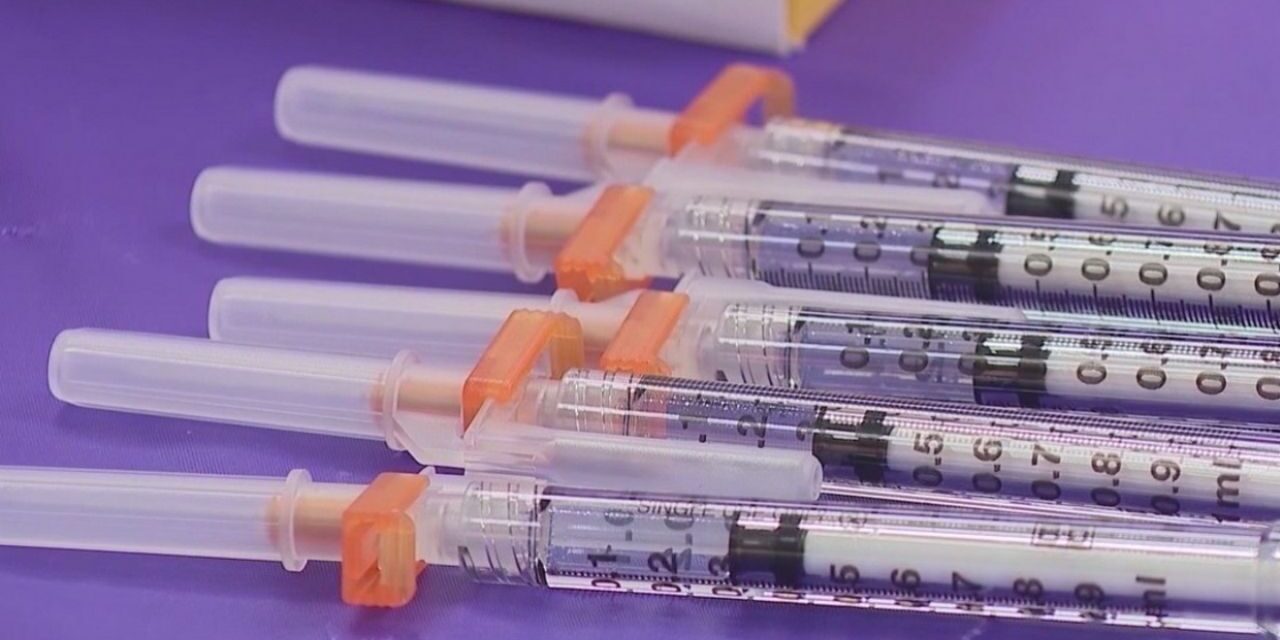

Now that the vaccines are being distributed, public health advocates say churches are key to reaching Black citizens, especially older generations more vulnerable to severe COVID disease. They have been hospitalized for COVID and died at a disproportionate rate throughout the pandemic, and initial data on who is getting COVID shots shows that Black people lag far behind other racial groups.

Black churches have also suffered during the pandemic. African American pastors were most likely to say they had had to delete positions or cut staff pay or benefits to survive, and 60% said their congregations hadn’t gathered in person the previous month, as opposed to 9% of white pastors, according to a survey published in October by Lifeway Research, which specializes in data on Christian groups.

Washington’s 75-member church is in Richmond, which has the highest number of COVID deaths in Contra Costa County, outside of deaths in long-term care facilities. The very diverse city, across the bay from San Francisco, also has one of the lowest rates of vaccination.

Offerings to Washington’s church plunged 50% in 2020 due to job loss among congregants, but he’s weathered the pandemic with a small-business loan and a second job as a general contractor remodeling bathrooms and kitchens.

Sabrina Saunders, founder of the One Accord Project, hosted monthly conference calls with up to 30 pastors in the Bay Area to connect them with public health officials and epidemiologists.

To combat misinformation, he’s been meeting virtually with about 30 other Black pastors once a month in calls organized by the One Accord Project, a nonprofit that organizes Black churches in the San Francisco Bay Area around nonpartisan issues like voter registration and low-income housing. Throughout the pandemic, the calls have focused on connecting pastors with public health officials and epidemiologists to make sure they have the most up-to-date information to pass on to their members, said founder Sabrina Saunders.

The African American church is an anchor for the community, Saunders said. “People get a lot of emotional support, people get resources, and their pastor isn’t just looked upon as a spiritual leader, but something more.”

And guidance is needed.

The share of Black people who say they have been vaccinated or want to be vaccinated as soon as possible is 35%, while 43% say they want to “wait and see” the shots’ effects on others, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation survey. Eight percent say they’ll get the shot only if required, while 14% say they definitely won’t be vaccinated. Among whites, the first two figures are 53% and 26%, respectively; for Hispanics, 42% and 37%.

Among the “wait and see” group, 35% say they would seek information about the shots from a religious leader, compared with 28% of Hispanics and 14% of white people.

Grassroots outreach to Black churches happens in every public health emergency, but the pandemic has hastened the pace of collaboration with public health officials, said Dr. Leon McDougle, assistant dean for diversity and cultural affairs at the Ohio State University College of Medicine. The last time he saw such a broad coalition across Black churches, medical associations, schools and political groups was during the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s.

“This is at an entirely different level, though, because we’ve had almost half a million die in a year,” McDougle said of the COVID pandemic.

Historically, no other institution in African American communities has rivaled the church in terms of its reach and the trust it enjoys, said Dr. Paris Butler, a plastic and reconstructive surgeon at the University of Pennsylvania Health System. Last month, he and a colleague spoke to leaders from 21 churches in Philadelphia to answer basic questions about how the vaccine was produced and tested.

“Being an African American myself, and growing up in a Baptist church, I understand the value of that trusted voice,” Butler said. “If we don’t reach out to them, we’re making a mistake.”

Leaders with massive social media followings, like Bishop T.D. Jakes, are also weighing in, publishing video conversations with experts including Dr. Anthony Fauci to inform followers about the vaccines.

Elders can influence the young, says Dr. Judith Green McKenzie, chief of occupational medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. (Photo: Daniel Burke/Penn Medicine)

Church attendance is waning among young Black adults, as it is for other races. But elders can set examples for younger people undecided about the vaccine, said Dr. Judith Green McKenzie, chief of the division of occupational medicine at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine.

“When they see their grandma go, they may say, ‘I’m going,’” she said. “Grandma got this two months ago and she’s fine.”

Encouraging vaccine trust is delicate work. The Black community has reason to be skeptical of the health system, said Eddie Anderson, the 31-year-old leader of McCarty Memorial Christian Church in Los Angeles. In one-on-one conversations, congregants tell him they fear being guinea pigs. The low vaccine supply also makes Anderson hesitate to recommend, from the pulpit, that members get the shot as soon as they’re able. He fears frustration with difficult online sign-ups would further sap motivation.

“I want to do that when it’s readily available,” he said. “I want to preach it, and then within a weekend a family can actually go get the vaccine.”

Despite the doubts and fears, Anderson said the majority of his 125-member congregation, about half of whom are senior citizens, want the vaccine, in order to be with loved ones again. One older member is desperately seeking a vaccine appointment so he can help his daughter, who is going through cancer treatments. But the online sign-up process is confusing and nearly impossible for his followers, Anderson said.

For now, he’s focused on asking several vaccinated members to write down everything about their experience and share it on social media. He also plans to record them talking about their shots — and to show that many people of different races were in the same vaccine line — and will broadcast the videos during church announcements.

While he can’t tell people what to do, Anderson hopes he can remove any potential spiritual barriers to the vaccine.

“My biggest fear is for someone to say, ‘I didn’t get vaccinated’ or ‘I didn’t get a test’ because it’s against [their] faith, or because ‘I don’t see that in the Bible,’” he said. “Any of those arguments, I want to get those off the table.”

Anna Almendrala is a correspondent for Kaiser Health News. She covers the business of health care and health care policy.

Boosting Your Immune System: What Works, What Doesn’t

The Best Fabrics for DIY Masks and How to Make Your Own