How Village Minds Addresses a National Crisis, One Bag of Groceries at a Time

By Marissa Evans

Natia Simone, founder of Village Minds, packs food to deliver in Chicago. (Photos: Billy Montgomery)

Natia Simone will never forget the pained look on the older woman’s face when she found out the Jewel grocery store wasn’t open.

It was the last week of May, and Chicago neighborhoods were still reeling from the ongoing protests after George Floyd’s death under the knee of a police officer in Minneapolis. Beyond the emotional unrest over yet another Black person dying at the hands of police, the protests had overrun the city with looting and property destruction where little was left unturned.

Simone, 43, a Chicago native, was one of many people independently driving around the area, slowly cleaning up the neighborhoods and small businesses. She came across a random group of volunteers near the Jewel store in the South Shore neighborhood telling an 82-year-old woman that the store was closed from the protests. The woman’s food stamps had been replenished for the month, and she walked to the store by herself.

Simone and the volunteers promised to deliver the woman groceries. The nearest open grocery store was too far to walk and unsafe given the protests. As Simone went to her car, another older woman stopped and asked if the store was open. Simone said her heart broke as the woman asked about other nearby stores that might be open. The woman drove away in search of groceries.

A few days later, Simone launched a Facebook page called Village Minds to allow people to ask for aid and soon she was fielding more requests from seniors needing assistance or mothers asking for milk for their babies. She thought she would help temporarily and quickly connect people with others who could assist them. But the need has not slowed down as Simone, her friends and family continue to volunteer their time under the now formalized organization.

“As we started hearing stories from these seniors about how difficult it was for them to get good food, I said this can’t stop,” Simone said. “This was a need that they had before the looting, before COVID-19, but now it makes it even more difficult for them to get food.”

Embed from Getty Images

Lines of cars like this one in Inglewood, California, snake through urban areas from coast to coast with people seeking food during the pandemic.

Black Women Are at “Center of Vulnerability”

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately ravaged the Black community with African Americans dying at 1.4 times the rate of white people, according to the COVID Tracking Project from Boston University’s Center for Antiracist Research and The Atlantic. This is particularly true in states with large urban centers like New York City, Newark and Detroit along with Washington, D.C. In Chicago, nearly 5,500 people have died so far, with 39 percent of the deaths being among Black residents, according to the city’s COVID-19 dashboard.

But the pandemic has also amplified longtime racial inequities when it comes to employment, income, health care, housing and who has the means to survive an unprecedented economic crisis. The pandemic has also exposed the severity of food insecurity in the United States with lines stretching for miles outside food banks and pantries as communities realize how fleeting food access can be for many households. Pop-up meal deliveries like Simone’s also dot social media posts and websites as communities pull together to find solutions.

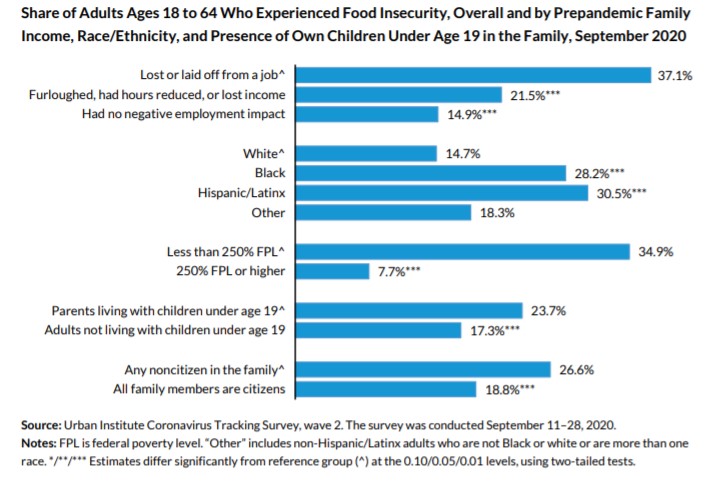

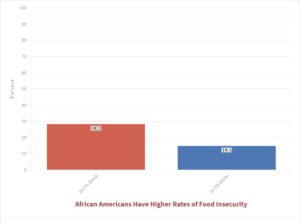

Food insecurity rates are 28.2 percent for Black adults, nearly double the rate of white households at 14.7 percent, according to a survey released last fall by the Urban Institute, a D.C.-based think tank.

Food insecurity rates are 28.2 percent for Black adults, nearly double the rate of white households at 14.7 percent, according to a survey released last fall by the Urban Institute, a D.C.-based think tank.

Part of the problem is people only think about food insecurity as a form of poverty, said Angela Odoms-Young, Ph.D., an associate professor with the University of Illinois-Chicago’s Department of Kinesiology and Nutrition. She pointed out that Black women are often vulnerable when disasters like the COVID-19 pandemic happen whether they have low incomes or college degrees. While education is touted as a means for upward mobility, Black women are taking on large amounts of college debt and losing their jobs — pandemic or no pandemic. Living paycheck to paycheck creates economic instability.

Whether they have low incomes or college degrees, Black women are forced to decide “Am I going to pay rent this month or buy food? Should I buy medicine or food?”

Single Black women with children in their household are also vulnerable to food insecurity, because they’re often the sole income provider, Odoms-Young said. They also may have family and friends who are struggling and cannot help them, especially with increases in the price of food during the pandemic.

“Black women are always at the center of vulnerability when you look at all of these things like Hurricane Katrina, COVID-19, Hurricane Sandy,” Odoms-Young said. “[They] end up being in a situation with a disaster that can put them in an economic disadvantage and have higher rates of food insecurity for not only that period, but years to come. So, the recovery becomes difficult.”

To help address hunger and other coronavirus challenges, President Biden signed the American Rescue Plan, which includes $12 billion for food programs.

Food insecurity often stems from unemployment, inadequate employment and living on little income, said Elaine Waxman, a senior fellow in the Income and Benefits Policy Center at the Urban Institute. Waxman pointed out that structural racism also drives the lack of assets and wealth that Black households often do not traditionally have like real estate, businesses and savings.

In Chicago, the unemployment rate was 7.9 percent by the end of April — half of what it was last year, but still among the highest in the Midwest, according to the latest data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

White families often accumulate more wealth over time than Black or Hispanic families do, and the gap widens as the populations age, according to an Urban Institute analysis of racial wealth gaps in 2016. The analysis found that by the time they’re in their 60s, white people could have over $1.1 million more in average wealth, or seven times more than Black people of the same age range do.

When looking at money earned over a lifetime by gender and race, Black and Hispanic women are also on the lower end. Another Urban Institute analysis found that for women between 58 and 62, the average Black woman can earn $1.3 million over a lifetime while the average Hispanic woman can earn $1.1 million. An older white woman can earn $1.5 million.

Waxman pointed out that the pandemic has put Black women on the frontlines as essential workers for jobs in grocery stores, nursing homes, retail, janitorial services and more. Mass wage cuts, furloughs and job losses has also deeply affected the service industry where Black women are also highly represented. Black women make up 11 percent of the front-line workforce despite only making up 6.3 percent of the workforce overall, according to a report released by the National Women’s Law Center in August.

“The people who lose a job in a recession are generally disadvantaged going forward, and that’s particularly true if that happens to you and you’re a Black woman in your 50s,” Waxman said. “As you get older, often your job opportunities are fewer so you have to start fresh. … At that point, that’s another disadvantage.”

Volunteers at Village Minds have made more than 3,650 pop-up food deliveries in Chicago since June. (Photo: Billy Montgomery)

‘Crappy Food’ or No Food in Forgotten Neighborhoods

If you want to understand food inequality, Simone says to go to a grocery store in a predominantly Black area and take a deep breath while standing in the middle of the produce section. Then do the same in a grocery store in a predominantly white area.

She said the difference comes down to the stores frequented by Black shoppers most likely having the stench of rotting fruit. It’s become a “glaring kind of problem” that stores are not trying to hide anymore.

“People are buying grocery from Dollar Tree or crappy stores that sell crappy meat next to cigarettes,” Simone said. ”So many people have been doing this for generations, because the neighborhood is forgotten.

Amid her quest to help her community get the food they need, Simone is also navigating her own grief. Her uncle died from COVID-19 in July, her father died in August and she has lost other aunts and uncles from her extended family.

One in seven people in Cook County, which encompasses Chicago, will experience food insecurity, according to Feeding America’s Map the Meal Gap Study.

A food insecure household might have enough food on one day and other days they may not know where their food will come from. Getting by might include relying on cheap nutritious calories that fill up their stomachs or a limited diet without much nutrition.

“In most severe cases it looks like reducing meals, skipping meals or going without food,” Waxman said.

The Urban Institute survey also found communities of color were generally experiencing severe food insecurity before and at the beginning of the pandemic. About 10.7 percent of Black adults reported skipping meals or going a whole day without food, compared with 6.9 percent of white adults, according to the report.

“The health disparities in nutrition and obesity correlate closely with the alarming racial and ethnic disparities related to COVID-19,” a group of medical experts warned last year in the New England Journal of Medicine. This includes chronic illnesses such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease that have increased morbidity and mortality among African Americans during the pandemic.

Throughout the pandemic, older adults have been deemed high risk for dying from the virus. Simone has found her older clients who are in senior or assisted living communities are largely fending for themselves now. Usual caregivers from social service providers have not been able to show up as often if at all due to COVID-19 protocols, and immunocompromised seniors are still scared to go outside in general especially with more and more maskless Chicagoans.

Since starting to deliver food to older adults in the area during the pandemic, Village Minds has provided more than 3,650 deliveries across the Englewood, South Shore and Bronzeville neighborhoods. Many of Simone’s clients are older Black women.

Some women were receiving food assistance through Meals on Wheels, a food bank or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), also known as food stamps, before the pandemic. Residents were sometimes receiving $17 in food stamp benefits for the month and cobbling together resources to survive. Meals from other providers were considered “worse than what you would give a dog” so residents would toss them out. When Simone offers canned goods and dry goods, she said residents will often tell her to bring them fruits and vegetables and save the canned goods for others.

She recalled months ago when she had plums in the boxes being delivered to buildings. One woman raved over the bright and juicy the plums.

“I was happy for her, but it broke my heart. She said: ‘We’ve been getting second-class food for so long; we forgot what good food tasted like,’” Simone said. “Nobody is giving them anything else.” Another time Simone had butter, and residents were overjoyed.

Certain deliveries require a CIA-style mission where Simone has “literally sneaked into buildings to get people groceries,” because she could not secure building supervisor’s permission. Seniors pass along “the grocery lady is coming” and what time she’s coming. As her rented U-Haul pulls up, residents stand outside waiting or run to schlep bags of groceries inside, sometimes coordinating extra bags for seniors who cannot leave their homes.

“The need, the hunger problem, the lack of food, is far beyond what I think people imagine,” Simone said. “There are a lot of people out here who are voiceless. … They don’t have anyone to advocate for them.”

- Hunger is a bigger problem than people think, says Natia Simone of Village Minds. (Photo: Billy Montgomery)

- Valentine’s Day deliveries. (Photos: Courtesy of Village Minds)

Long-Term Solutions Are Needed to Address Food Insecurity

Simone’s family and friends often help with deliveries and unloading the truck. She also has partnerships with Premiere Produce, a local store that helps provide fruit and vegetables, and Lakeview Pantry, a food pantry in Chicago that helps make food boxes for Simone’s organization.

Kellie O’Connell, CEO for Lakeview Pantry, said the organization was happy to partner with Village Minds. “It really helps lift up other leaders to serve their communities however they seem fit,” O’Connell says, while the pantry helps behind the scenes. The emerging issue around how to feed seniors during the pandemic had been on the pantry’s radar and partnering with Village Minds has made helping this vulnerable population possible.

The pantry serves nearly 65 percent people of color and since the pandemic they’ve seen an increased need as people struggle to make ends meet. More than half of the people they’ve served in recent months were first-time visitors.

“It’s a lot of people who are probably living paycheck to paycheck already and suddenly finding themselves in a tough spot,” O’Connell said. “It’s: ‘Am I going to pay rent this month or buy food? Should I buy medicine or food?’”

Odoms-Young said people assume food distribution will solve food insecurity. While handing out canned goods and groceries through pop-up charitable donations is helpful, she said it’s not enough. Programs like the Women, Infants and Children program and SNAP can stabilize families, but there needs to be solutions to help them long term.

Those solutions include employment, wealth building, job training, expanding employment opportunities and providing educational opportunities without people needing to incur a lot of debt.

“The idea of charitable food to address food insecurity is wonderful but that’s the immediate need,” Odoms- Young said. “The long-term goal is we have to address root causes of food insecurity and that means getting at the root of addressing poverty, unemployment and the factors that drive people into food insecurity.”

For now, Simone is determined to buy a location where she can have freezers and store food, purchase a refrigerated truck for deliveries and work toward a contract with the U.S. Department of Agriculture. But she loses sleep some nights worrying that she forgot to deliver food to someone.

“For senior citizens that has lived their life, been responsible, done what they had to do and to be in the fourth quarter [of life] and have to be worried about food is so sad to me and it’s so unfair,” Simone said. “I’m going to do what I have to do to help.”

Marissa Evans is a journalist based in Minneapolis. Her article on the impact of COVID-19 in urban areas is the second in a FierceforBlackWomen.com series supported by the Solutions Journalism Network. The series opener focused on rural areas in the South.