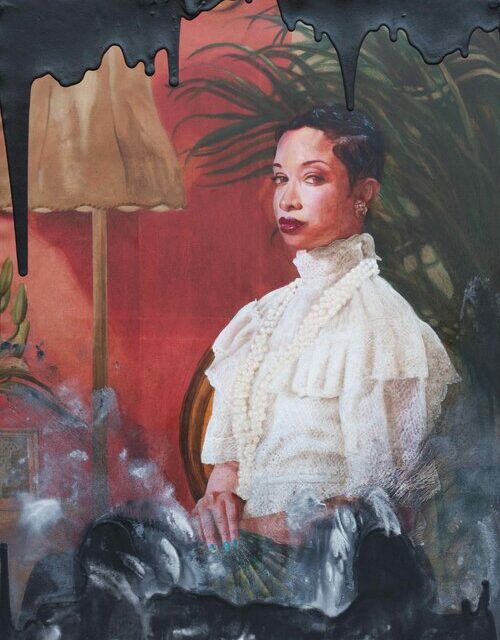

The woman’s modest, dignified posture in the artist’s interpretation of Mary E. Jones Parrish — coupled with a serene, knowing gaze — evinces a famous, enigmatic counterpart. Yet this woman’s countenance takes us beyond enigma into a world that is knowable and all too real, for these eyes saw fire rain from the sky in Tulsa.

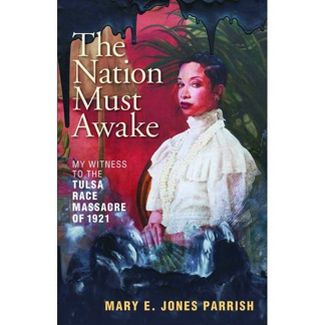

As a descendant of Tulsa Race Massacre survivors, I find great personal meaning in Ajamu Kojo’s art, “Black Blood, No.3: In the Spirit of Mary Elizabeth Jones Parrish,” on the 102nd anniversary of the catastrophe. The Brooklyn-based artist’s portrait of my great-grandmother is featured on the cover of her book, The Nation Must Awake, and in Kojo’s digital exhibit, “Black Wall Street: A Case for Reparations,” which was also on view last year at Montclair State University Galleries in New Jersey.

On the evening of May 31, 1921, Mary Parrish settled in with a good book after teaching class in her private secretarial school. Business was booming in Tulsa, and money flowed like the oil that fueled the city’s growth. You can see it dripping down Kojo’s painting, viscous and sticky. Young women wanted training for office jobs, and the 31-year-old mother saw this need and opened the Mary Jones Parrish School of Natural Education to help fill it. Although the Greenwood District, where African Americans lived, operated like a separate town, it was the segregated part of Tulsa and shared in the city’s prosperity. Mary Parrish taught typewriting and shorthand by day at the Hunton Branch of the YMCA and taught evenings at her own establishment in the building where she shared an apartment with her little girl — the Woods Building at 103–1/2 Greenwood Avenue.

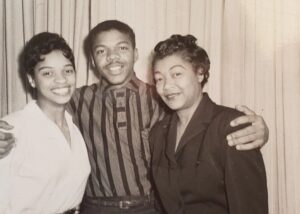

Anneliese Bruner’s father gave her a book about the Tulsa Race Massacre that would change her life. She later learned that the author, her great-grandmother, and her grandmother, Florence Mary Parrish Bruner, far right, had survived the tragedy. Her parents, Jeraldine Bruner and William Bruner Jr., are on the left. (Photo: Bruner Family)

That evening’s class of typewriting students had been dismissed, and mother and daughter were passing time before bedtime. As the young business owner became engrossed in her book and her daughter was amusing herself by looking out the window onto the avenue on that warm spring evening, the little girl’s voice rang out urgently.

“Mother, I see men with guns,” 7-year-old Florence Mary cried. That moment exploded into a series of cascading events on which their survival hinged.

Upon hearing her daughter’s cry, Mary rushed to the window and saw that what her little girl said was true. Men in the street carried long rifles, and bullets were flying. She instructed little Florence Mary to lie down on the duofold sofa bed, praying that it would prevent any bullets that might penetrate the windows or walls from harming her child.

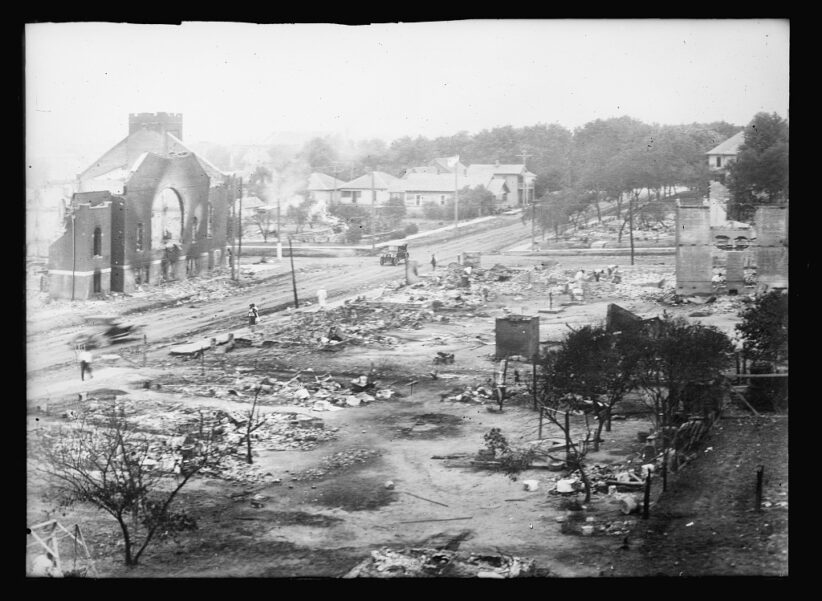

During the next hours, gunshots and fire systematically eviscerated the neighborhood, driving out its residents. Through the night and into the next day, vigilantes marauded through the district, setting homes and businesses ablaze as they advanced on the community. The invaders would shoot at the fire brigade when it arrived to put out the many fires, preventing the firefighters from saving Greenwood. The young mother was frantic about how to save herself and her young daughter.

“I took my little girl in my arms, read one or two chapters of Psalms of David and prayed that God would give me courage to stand through it all,” she writes in her book, originally published in 1923 and now titled, The Nation Must Awake: My Witness to the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921.

“I took my little girl in my arms, read one or two chapters of Psalms of David and prayed that God would give me courage to stand through it all,” she writes in her book, originally published in 1923 and now titled, The Nation Must Awake: My Witness to the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921.

Ultimately, Mary Parrish decided that it would be better to die in the street by gunfire than to remain where they were and be incinerated, as many others were in their homes, possibly as they slept. Her close neighbors had already fled, but she had waited, watching to see whether the attack would stop.

The pair fled their apartment — and their comfortable lives — to join other refugees escaping the advancing corps of marauders. The sights became emblazoned in the survivors’ minds: White men with long guns dangled out of car windows, shooting as they drove by; Black men were tied and dragged behind cars; drivers gleefully mowed down fleeing residents; people were shot or burned in their homes; men in planes flung turpentine bombs and dynamite sticks out of open cockpits onto buildings below, raining down destruction. These were the events that eyewitnesses would later recount to Mary Parrish as she reported their stories for her book.

Chaos and fear hung in the air as bodies laid in the street. Terrorized Black citizens fled on foot or, as in the case of Mary Parrish and her daughter, on the back of a truck, or in cars. Some were too traumatized to ever return to Tulsa and fled permanently, becoming internally displaced persons scattered throughout the country. Postcards and other images from the time depict White vigilantes herding groups of Black people like cattle or standing over the bodies of slain Black men. One ruffian with a rifle slung casually over his left shoulder like a familiar garment, holds another firearm in his right hand, a cigar dangling from his lips. One imagines the tobacco smoke curling up into his cruel, squinting eye.

The juxtaposition between the idealized version of the American majority population and the savagery expressed in the two days of violent abandon in 1921 Tulsa reveals a crucial tension in the American psyche. The propaganda film The Birth of a Nation was released in 1915, six years before the massacre, and it concretized the preferred narrative of Black people as unintelligent, irredeemable savages whom the white man had to civilize, and whites as stewards of a great civilization whose future had to be protected from violent, unworthy Blacks. In the popular imagination informed by the film, Black people were poised to overrun the government and country; they needed to be stopped in order to preserve the natural racial hierarchy of white people at the top of the social order, controlling the money and wielding the power.

Reinvigorated by the popular movie, the Ku Klux Klan had begun to gain a hold on local governments in Oklahoma starting around 1920. Their influence on the white community would have grown by 1921. In contrast to the known vice in this monied corner of the country, a strong moralistic ethos was prevalent throughout Tulsa. The so-called better people of both races decried the prostitution and bootlegging that thrived in the booming town, and the concomitant race mixing around these “evils” contributed to the tension between white and Black Tulsa.

The accident between Dick Rowland and Sarah Paige, the elevator operator whom the young man stumbled into, causing her to scream in alarm, became the catalyst for the massacre. Inflammatory reporting by the Tulsa Tribune spurred an angry mob to attempt to snatch Rowland from the jail where he was kept after his arrest on assault charges. Their first attempt to kidnap him was thwarted by African American veterans of the same world war that white American veterans had recently fought in a fractured Europe, where fascists sought to seize land and power. The Black vets were turned back by the sheriff, who declined their offer of help and guaranteed Rowland’s safety.

As the mob grew, the Black community feared that the sheriff’s assurances were insufficient. They returned to the downtown jail in greater numbers than before, and the worst happened. A White man, outraged at the audacity of the Black veterans, tried to grab the gun from one of the men. A tussle ensued, shots were fired, and a skirmish that would grow into the massacre commenced.

The natural drive to find reasons for the violence ascribes it to several causes: the economic anxiety of unemployed white veterans from World War I; land lust by developers who had long coveted the property the Greenwood District occupied; the general climate of racial animus; the defense of the presumed violation of white womanhood; economic envy of Black prosperity. All these surely played their part in this American tragedy. At the core, however, is that what happened in Tulsa was possible because of the power disparity between the white and Black actors in this story. The powerful set the rules of engagement and decide how or whether to apply accountability.

White mobs killed 300 Black residents and destroyed about 1,000 homes, churches, businesses and other institutions in the Black Wall Street during the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Against this landscape, the intrepid, resolute Mary Jones Parrish pushed back against any negative prevailing narrative. She had arrived in Tulsa from Rochester, New York, after completing training at the Rochester Business Institute. But she was not alone in pushing back. Mary Parrish made her home in Tulsa because of the cooperation that she witnessed among Black businessmen and businesswomen, and the broad sense of community and purpose. Tulsa’s Black Wall Street exemplified the best of what Black America offers to the nation.

America, however, was not wholly accepting of her African American citizens, forcing them to continually struggle for full citizenship rights, the metric of a well-functioning democracy. Part and parcel of the suppression of rights has been the willingness by groups of white Americans to engage in the most visceral form of political terror. As in the case of the mob that tried to snatch Dick Rowland, lynching was an American scourge that served as both warning and extralegal punishment in a capricious form that could be unleashed on Black people on a whim. It was a powerful tool in maintaining white primacy. White people were sometimes the victims of lynching, but most victims of these brutal murders were Black.

After over 100 years of failure, Congress finally passed a federal anti-lynching bill in 2022. In her book, Mary Parrish lauds U.S. Rep. Leonidas Dyer, R-Missouri, who had witnessed the East St. Louis massacre of 1917 and sponsored anti-lynching legislation in Congress, H.R. 11279, on April 18, 1918.

“The Dyer Anti-Lynch Bill’s passage will be a glorious victory towards making the United States safe for its peaceful, law-abiding Black citizens. We, as a race, especially, doff our hats to Mr. Dyer, the originator of this bill, and to the noble men of Congress who voted for it.”

Unrepentant, wanton violence and the drive to dominate continue to steer politics. We see that today in the war of aggression that Russia is waging against Ukraine in a destabilizing impulse for irredentism. Russia’s eye toward the past is a rapacious, imperial one, revisiting the horrors of the past on the citizens of today’s Ukraine. In the world Mary Parrish inhabited, today’s past horrors were contemporary ones:

“Americans have been loud in the denunciation of the pogroms in Poland, of the massacres in Armenia and Russia and Mexico, and they were ready to go to war to avenge the victims of the barbarous German war-lords, but unless we can create a public sentiment in this country strong enough to restrain such intolerant outbreaks as Tulsa has just witnessed, we shall be unable in the future to protest with any moral weight against anything that may happen in less favored parts of the world. … The great holocaust of June 1, 1921, had left the colored section in ashes and ruins. Where imposing business buildings and stately mansions had stood just a few days before were now nothing but heaps of ruins and charred things burned beyond recognition. The people were in confusion and, in many instances, utter helplessness.”

The helplessness of the people she describes parallel that of any refugees fleeing war in their land. Though on a limited scale, Tulsa’s Black Wall Street experienced war. The scourge of vigilantism combined with racial animus is an explosive mix.

Mary Parrish’s eyes looked toward a future where democracy was more than a catchword, with the hope that people could live in a country with equal representation under the law and equal opportunity to contribute to the life of their nation.

Click here for a tour of Ajamu Kojo’s Black Wall Street: A Case for Reparations.