Young sisters want Atlanta’s Keisha Lance Bottoms to bring more than her Black womanhood to City Hall

Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms admits that Spelman College students’ decision to protest her as commencement speaker to make a statement about gentrification “hurt me deeply” as a Black woman. Her solution? Spread the message that on her watch, economic development in the so-called Black mecca is not a plan to push Black people out of Atlanta: “Let’s have a conversation about how we make sure we’re smart about it.”

By Charlayne Hunter Gault

For Black Women Unmuted

Atlanta is known for many things, including being one of the birthplaces of the Civil Rights Movement aimed at ending the longstanding and ongoing lie of separate but equal. The movement led to dramatic changes in the city, including the election of six Black mayors since Atlanta elected its first, Maynard Jackson, in 1973. Today, the city is known as the Black Mecca, with some even calling it The Real Wakanda.

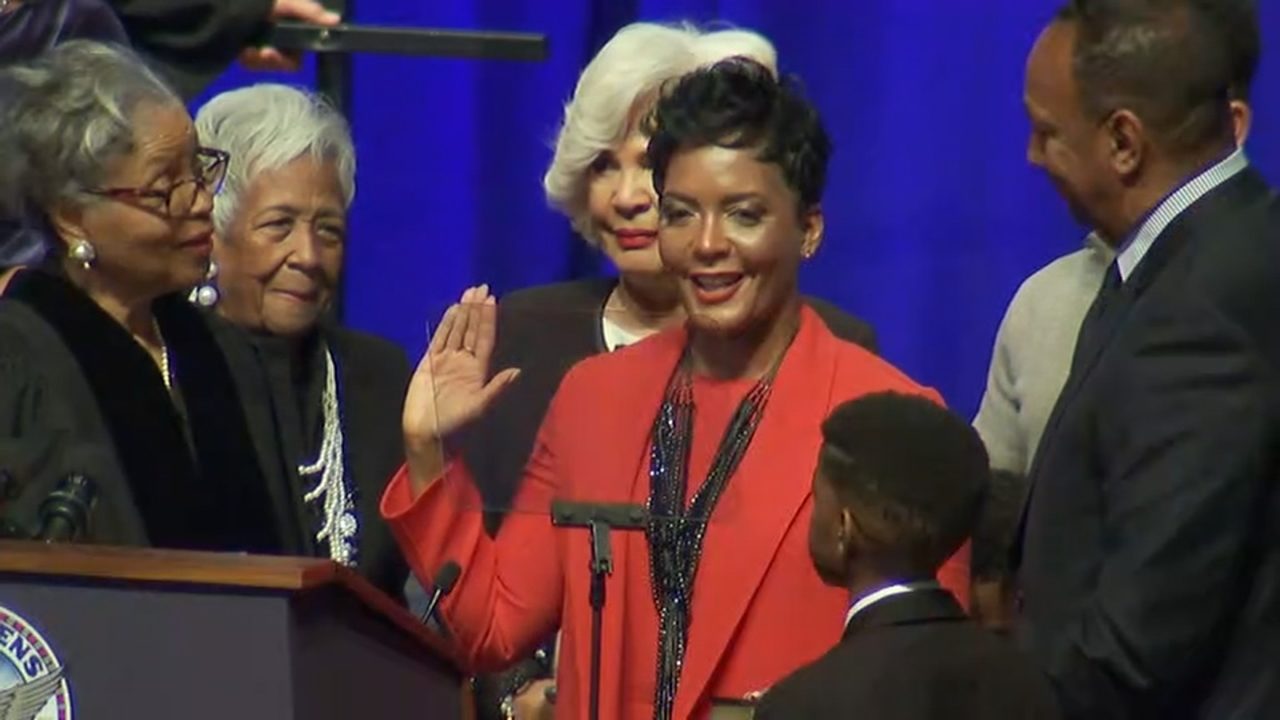

On that, the jury is still out. But despite a tight race, an overwhelming Black turnout in the bruising 2017 election led to 49-year-old Keisha Lance Bottoms being sworn in on January 2, 2018, as the second Black female mayor of this city where Black women make up a large share of the voters. Like the Civil Rights Movement of my day some 58 years ago, a younger generation of energized Black activists is insisting on holding the mayor accountable, saying that having a Black woman mayor may not be enough to guarantee Atlanta’s status as The Real Wakanda.

The latest clash emerged in stark relief when several students pushed back against Mayor Bottoms being chosen as the graduation speaker at historic Spelman College, the 138-year-old institution with a motto of empowering African American women “to engage in the many cultures of the world and inspire a commitment to positive social change through service.”

As Eva Dickerson, a member of this year’s graduating class, told me recently:

“I have no qualms admitting that Mayor Bottoms is a progressive. I also have no qualms highlighting the fact that we’re not progressives, we’re radicals. We’re student organizers so there will always be that clash. And in that clash is where growth happens.”

EDITOR’S NOTE FROM BLACK WOMEN UNMUTED

According to the Center for American Women & Politics, seven of the United States’ largest 100 cities are run by Black women mayors. Two of these cities are state capitals, one is the nation’s capital, and their populations range from 225,000 to 2.7 million citizens. All across America, Black women watched these mayors take over City Hall with great interest — and remain eager to hear more about how they are faring.

We at Black Women Unmuted are responding to that desire with “Madame Mayor,” our series exploring governance issues in Atlanta; Baton Rouge; Charlotte; Chicago; New Orleans; San Francisco and Washington, D.C. This series is being presented with FierceforBlackWomen.com, a founding content partner.

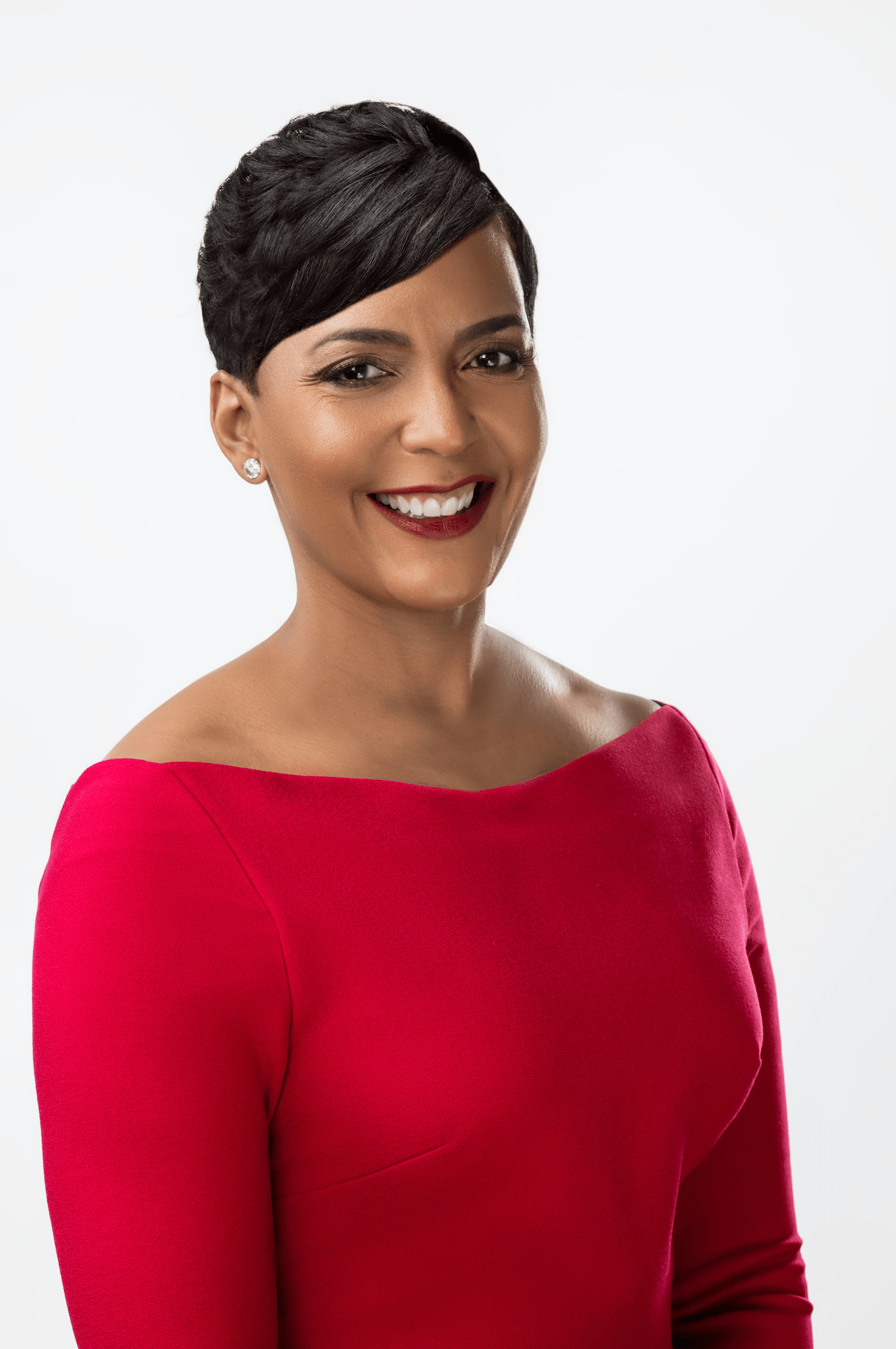

First up: Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms, who spoke with legendary journalist and fellow Atlanta native Charlayne Hunter-Gault about her struggle to balance the city’s economic development needs against concerns that gentrification spurred by that development is pushing out the poor.

A History of Activism

Some of the Spelman students who protested Mayor Bottoms’ choice as commencement speaker were unhappy that they had not been consulted about the speaker, as seniors had been in the past.

So on a day when Spelman’s sprawling lush green campus was empty, except for a few summer students lounging in hammocks or casually strolling along its paved walkways focusing intensely on cell phones, I met Eva Dickerson and another protestor, Clarissa Brooks, in the Camille Olivia Hanks Cosby Building that houses the College’s Women’s Resource and Research Center, to learn more about their protest. Eva had graduated and Clarissa was a senior with credits to complete.

Like many Spelman women, the students had spent many hours in the center during their four years at Spelman, their current activism inspired and affirmed by their professors and by the history of creative women such as Nikki Giovanni, Toni Cade Bambara, Gwendolyn Brooks, Mari Evans, Pearl Cleage, Sonia Sanchez and Johnnetta Cole, the first Black woman president of Spelman.

Against that backdrop, the two students laid out larger reasons why students protested having Mayor Bottoms as their speaker. “To me,” Brooks said, “it meant that Spelman supported the mayor’s lackluster investment in Black Atlanta and working-class Atlanta.”

Brooks added that opposition to the mayor dates back to some of the 10 years when Bottoms, a former judge who had also practiced law and served on the City Council when her predecessor, Kasim Reed, was mayor. One major issue then, as now, is the growing gentrification of the city.

On one occasion involving an area called Peoplestown, Spelman students like Brooks joined local community organizers in an attempt to get a Community Benefits Agreement that would have prevented rising property values from driving out long-term, low-income, mostly Black residents, and necessities like their local grocery store.

As Brooks put it, “We pushed and we asked and when we had residents go and speak and try to plead with her to understand why this agreement was important to Peoplestown and she didn’t. And that legacy and these feelings for myself were still there.”

Brooks acknowledged that Mayor Bottoms had done some positive things in the city and was attempting to be more transparent.

“And while that’s really great, there are still Black folks in the city dying. There are a lot of poor Black folks who are drinking contaminated water and living in housing that’s not OK and who are being pushed out of their own communities. So while I enjoy and understand transparency and the push towards a more accessible mayor, actions are gonna affect the everyday lives of Black folks and that is not changing. I think it will come with a lot of continued organizing.”

‘It Blew Me Away’

Spelman President Mary Schmidt Campbell, who has led the college for four years, told me that initially, she was shocked at the reaction to Bottoms’ selection as commencement speaker, saying the pushback against the mayor took her “completely by surprise.”

“I thought, ‘Wow, this is gonna be a home run and so it blew me away.’”

Social media around campus had erupted with the hashtag #NotKeisha.

Campbell added: “I was surprised at the fierceness of that opposition.”

At the same time, Campbell said she also understood the history of Spelman women and the most important part of the institution.

“The fact that women are educated to be leaders and being a leader means finding your voice and using it to speak up for things you care about …and so if you look at the history of Spelman, the hymn itself and the words of the hymn, which are ‘undaunted by the fight,’ I mean it says we are women warriors who are going to be going out in the world to have a fight. So I would say if there are protests it means that people were trying to shine a light on something.”

President Campbell called a meeting with some of the student leaders and protesters, followed by a meeting between them and Mayor Bottoms.

“To a great extent the students are raising real issues,” Campbell acknowledged. “If rents go up people will get evicted. If new business comes in they may offer competition that threatens existing businesses. If you say, ‘I’m gonna make the place safer,’ how do we know that it means we are gonna make it safer for Black people?”

At the same time, President Campbell said she believed the students and the mayor want the same thing. But she also said: “The jury is still out.”

Gentrification Is Alive and Growing

Peoplestown isn’t the only area in Atlanta where gentrification is alive and growing. It’s happening in the West End area near where I grew up. On the way to speak with the mayor, I stopped in at the home of Earl Picard, who bought a house there some 42 years ago when it was an all-Black neighborhood. He remembered when he first moved into the community.

“So the housing stock was very old… A lot of older people were living in the houses and they didn’t have the means to renovate,” Picard said. “So the housing stock was declining. Just an old neighborhood getting older and declining. That all began to change in the 80’s.”

I asked Picard if he thought it was fair when people like the Spelman students and other activists criticize the mayor on gentrification. He believes it’s not fair to blame her, “because… she probably was still in high school when all of this started.”

Picard took me on a little tour around his neighborhood and the signs of change were everywhere. Every now and then I could see an older Black resident sitting on her porch. But Picard says that’s changing.

“They coming up and buying all of these little houses, rehabbing them and putting them on the market as quickly as they can,” he said.

“Everywhere you look?” I asked. “Would you say that most of the people who are renovating are white?”

“Well the ones who are moving in,” Picard replied. “The speculators are renovating and then they’re buying them.”

One of the more telling signs of the gentrification of this area was a recently added restaurant that Picard showed me, Slutty Vegan. The owner is a young Black woman, a graduate of Clark Atlanta University named Pinky Cole.

“The first day she opened a thousand people showed up. She opens at 3 o’clock, and you come here at 2 o’clock and the line’ll be all the way down to the light,” Picard said.

Cole’s restaurant may be a symbol of gentrification in the West End to some but for her, setting up shop there was hardly about taking advantage of soaring home values or gentrification’s other side effects. She told Forbes magazine in July:

“This neighborhood and I go way back, and bringing vegan options and food awareness to this community for which I care so deeply has been one of my life’s dreams. Opening the conversation on vegan food options for people who have never considered them in this community that has such high numbers in hypertension, cholesterol, obesity, and a host of other food-borne ailments is momentous. I am humbled daily by the weight of the opportunity, and I’m motivated by its seriousness.”

Inside City Hall

Later that day, I arrived at City Hall, a building seemingly unchanged from my Atlanta days.

Except once inside and up the winding stairs and into the mayor’s offices on the second floor, there’s a different look … Black art on the walls throughout the rooms leading to the conference room where I met the mayor, who greeted me with a handshake and a smile.

But soon, her smile faded as she answered my questions about how she felt about the #NotKeisha protest from the Spelman students and the subsequent meeting with them.

Although she told me she thought the meeting with the students “went well…” she also went on to say: “The Spelman conversation hurt me deeply because the reason I’m mayor is that we wanted to make our communities better.”

“What hurt me was the narrative attached to why they didn’t want me to speak. That I didn’t care about Black people and that I didn’t care about gentrification and that I was ignoring the needs of our community. And all we do every day is talk about the work on equity. And to have stood at a Town Hall meeting in Buckhead, and to have been booed when I talked about closing the city jail and putting a 24-hour day-care center and job training to be booed in Buckhead and then be shunned at Spelman…”

“And Buckhead being mostly white,” I added.

“That was shocking!” Bottoms continued. “It really said to me we have a group of well-intentioned bright young women who were misled and misinformed.”

The mayor said she tried to correct various misimpressions, including that the city was responsible for gentrification that included the longtime mall in West End. She said she explained that the city didn’t own the mall, but a white private citizen whose name she gave them. She also said she told them:

“Redevelopment is happening throughout the city and the biggest challenge we have is making sure that we don’t stop the development but we don’t let it be at the expense of people… our legacy residents in the city. People like my family that … it’s about preserving our neighborhoods, allowing people to remain in their homes with dignity.”

‘Creative and Thoughtful’

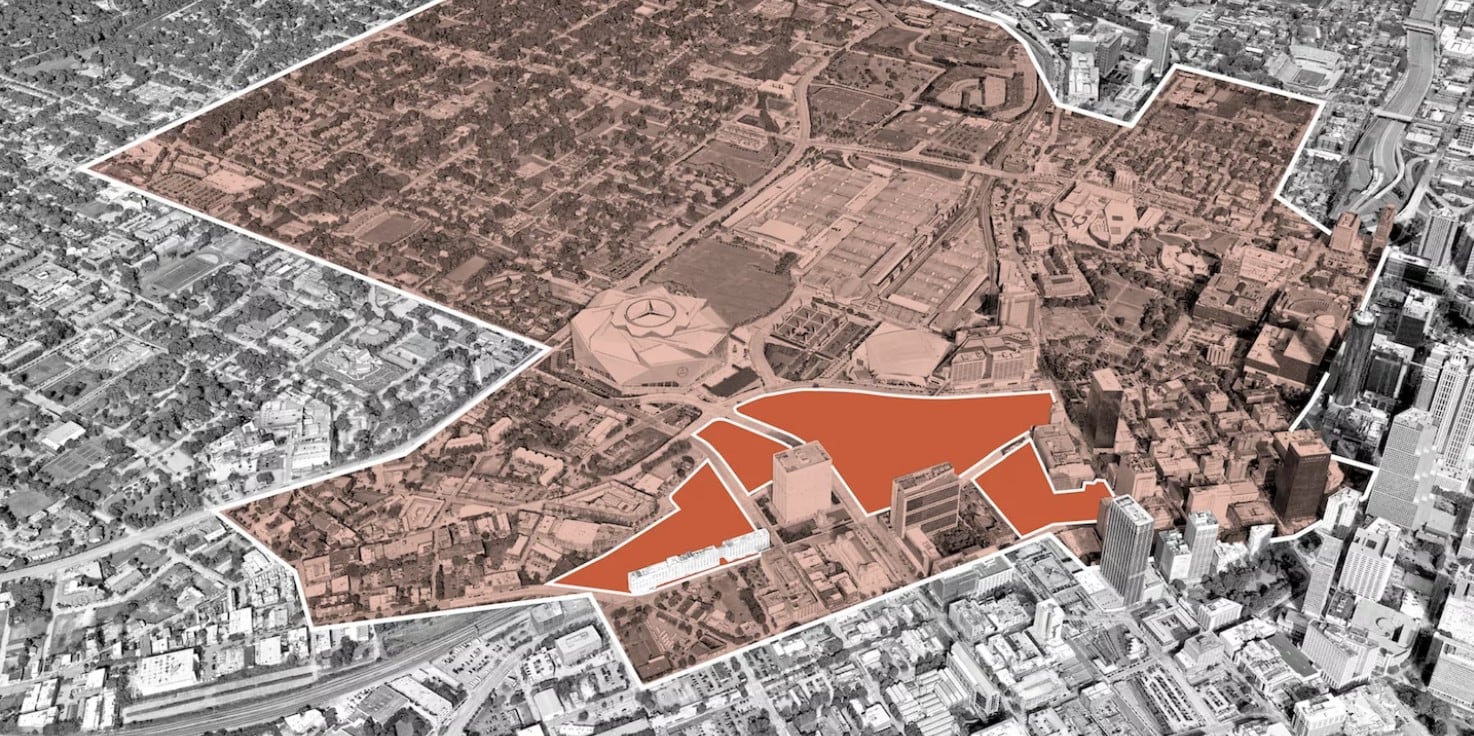

The mayor went on to talk about how she and her team are being “creative and thoughtful” about redevelopment plans…including redeveloping an undeveloped area in downtown Atlanta called The Gulch.

“So with the Gulch, for example, which will be a 20-year redevelopment creating 40 new city blocks. We have … a $28 million Affordable Housing Trust Fund that’s coming with that … 20,000 Affordable Housing Units and a housing plan to be preserved or created by 2026 that we’ve approved. And we are appointing a Chief Housing Officer. … And we have one of the most aggressive housing plans in the city.

“So what I said to them is, ‘we can’t stop gentrification,’ but I said to them, ‘many of you in this room are gentrified. Gentrification is not always about race. Gentrification is an economic conversation. So when you move into the West Side of Atlanta and you are in your nice West Side apartment, you, too, are gentrifying. So please understand exactly what gentrification is, what’s your role in it and then let’s have a conversation about how we make sure we’re smart about it.’ ”

Another issue the students raised was the closing of a homeless shelter downtown. The mayor told me she explained that the place where the homeless were living was in a warehouse that was antiquated and unhealthy and that there was no control over either the food they were being fed or the trash being left in the streets.

And while she said they didn’t enforce the rule against feeding the homeless downtown, they came up with some new designs they considered healthier and more appropriate.

“What we know now is that to tackle the issues of homelessness and achieve what we call effective zero as we have with our veterans, you have to be very specific and targeted. So you can’t provide services to an LGBTQ homeless youth in the same way you would a veteran. Two different sets of underlying issues, two different sets of underlying social services needed. So we’ve gone to a scale model where we try and put people in appropriate housing based on what we believe their challenges are and then deliver those services to their doorstep …. so that we deal with the issue of homelessness with dignity.”

One example Mayor Bottoms gave was the renovation of a downtown hotel to house the homeless where social services can be brought to their door. Another hot-button issue the students raised was police violence in the city, a problem not unique to Atlanta. But in Atlanta, in the past year, two unarmed Black men have been killed by police, one working with an FBI Fugitive Task Force.

Since the Feds prohibit local police from wearing body cameras in joint operations, the mayor said she has pulled her police officers out of the Federal Task Force and has insisted Atlanta police wear body cameras that come on automatically. Some of the protestors wanted the Black police chief fired, but Mayor Bottoms refused.

The mayor also said there were actions she has taken that speak to her commitment to issues that disproportionately affect Black people, like eliminating jail time for people who can’t pay $200 cash bail for minor traffic offenses and, as a result, have had to spend three months in jail.

She also pointed to closing the City Jail and setting up training programs for many of those formerly incarcerated, with some of them serving as instructors. And she said Atlanta is now “reimagining” its jails.

”We have this 450,000-square-foot facility that was once a place of mass incarceration that we are looking to transition into an equity center so that we can provide needed services in a physical space for people to get the tools they need to succeed … and part of the team of people who will be working in this facility are people who spent time in that facility and they will talk to us about what they needed to get on their feet and what they wish had been available to them.

“I think that’s a change of direction for us as a city and what I really hope will be a model for the rest of the country.”

‘In the Service of Others’

The mayor also added that she was opposed to the way the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, aka ICE, was handling people of color detained at the U.S. border with Mexico, taking them to jails in cities like Atlanta. She terminated their contract and asked that the detainees be removed, a move she is hoping other cities will adopt.

The mayor also alluded to other things listed on her website that includes the establishment of the city’s first fully-staffed Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, the appointments of an LGBTQ Affairs Coordinator and a Human Trafficking Fellow, and the rollout of what it states is the most far-reaching financial transparency platform in the city’s history – Atlanta’s Open Checkbook.

The website also states that …

Under Mayor Bottoms’ leadership, the City of Atlanta led the historically successful staging of Super Bowl LIII, which included unprecedented community benefits – a $2.4 million renovation of John F. Kennedy Park on Atlanta’s Westside, more than 20,000 trees planted throughout the community and the seamless coordination of 40 federal, state and local public safety agencies.

I asked the mayor why did she think there was so much pushback, despite all that she believed she was doing for her people. She took a long pause, then said: “If I had to peel it back, I think life is hard on us and we sometimes project it on one another. We bring a lot of resentment we get from other places into how we deal with one another.

“We didn’t have the luxury of embracing each other in the way that white women have had.”

When I asked Mayor Bottoms if she thought she had reached the young protestors, she told me:

“I think in true young women fashion they listened attentively. Some pushed back. It was a very polite conversation. Some who didn’t understand — not a lack of understanding of the issues but didn’t understand why some of their classmates were pushing back against me as an African American woman and some who were just interested in graduating.”

But she then added: “My biggest takeaway is we’re not communicating with the people we need to be in community with.”

To that end, she is now doing a Q&A once a month with Georgia Public Broadcasting, accepting questions from listeners through call-ins and on Twitter. And she says she is focusing more on communicating with younger people using Instagram, Facebook and YouTube, “because we know what the narrative is on the 6 o’clock news and they’re not watching the 6 o’clock news.”

And so it was on Spelman’s graduation day, as the protestors and other graduating students sat quietly, when the mayor, outfitted in full academic regalia, spoke directly to the students for almost 15 minutes. She ended her speech to graduates of the Spelman Class of 2019 with these words:

“On those doubtful days, when you know that you are walking into the fire, as I anticipated today, and during those moments when you are misunderstood, or even misrepresented, simply because of who you are, remember the words of Audre Lorde, who said, ‘When I dare to use my power in the service of others, it becomes less and less important whether or not I am afraid.’ ”

Charlayne Hunter-Gault

Credits: Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms and The Gulch/City of Atlanta; Commencement/Spelman College; Ayokunle Odeleye sculpture/Peoplestown Revitalization Corp.; “State of the City” video/11 Alive; Charlayne Hunter-Gault.